Copenhagen based artist and co-founder of CHART, David Risley, reached out to artist and writer Brad Phillips to get his reflections and views on some of the artists exhibiting at CHART 2021. Read his reflections on bodies, bodies of work and the body making art in this piece interviewing the works of artists Anastasia Bay, Paul McCarthy and others.

*Throughout this essay, the Covid-19 pandemic will be referred to as ‘The Plague’.

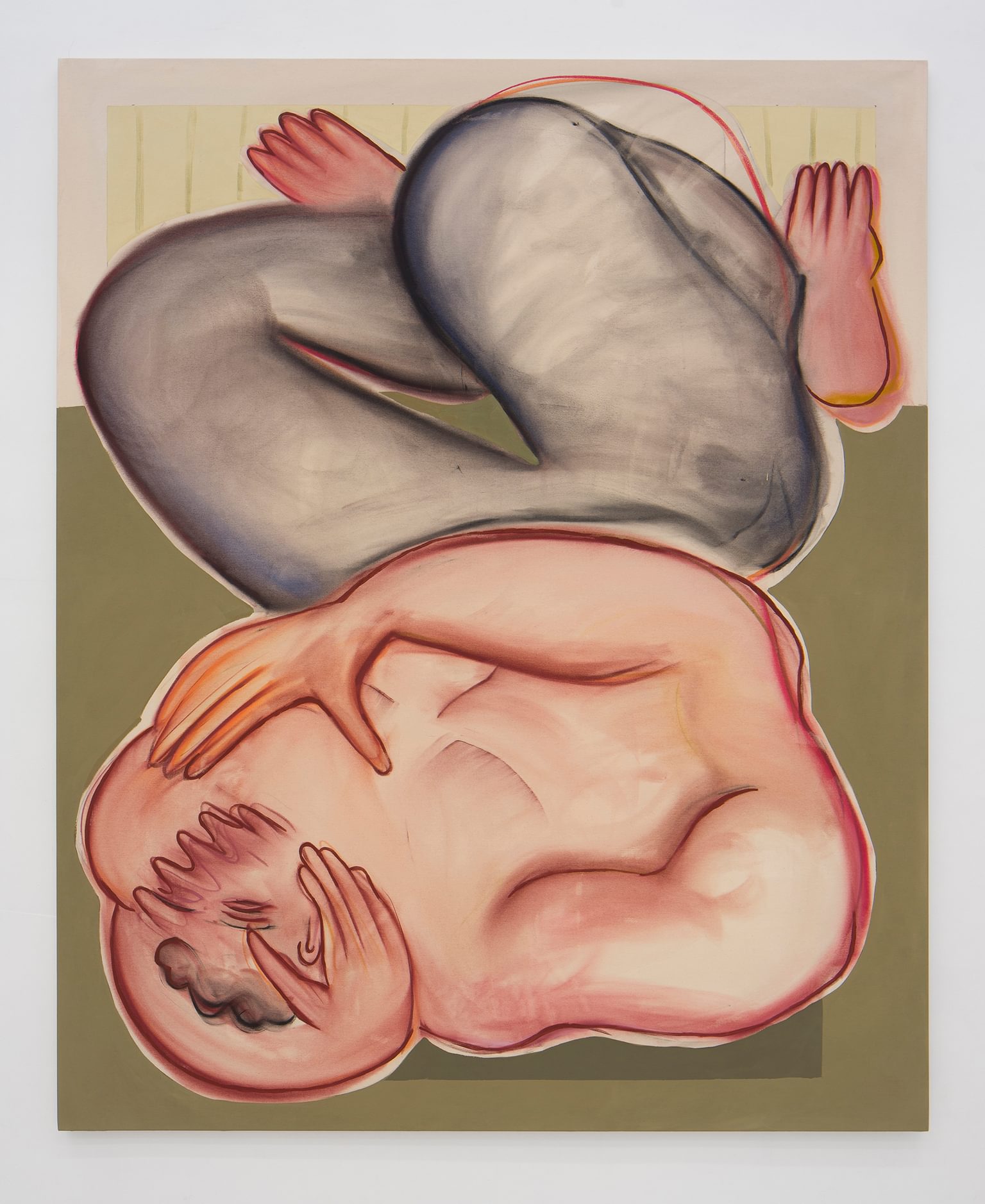

Anastasia Bay, A Song of Love (3), 2021, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 200 x 160 cm

Courtesy of the artist and NEVVEN

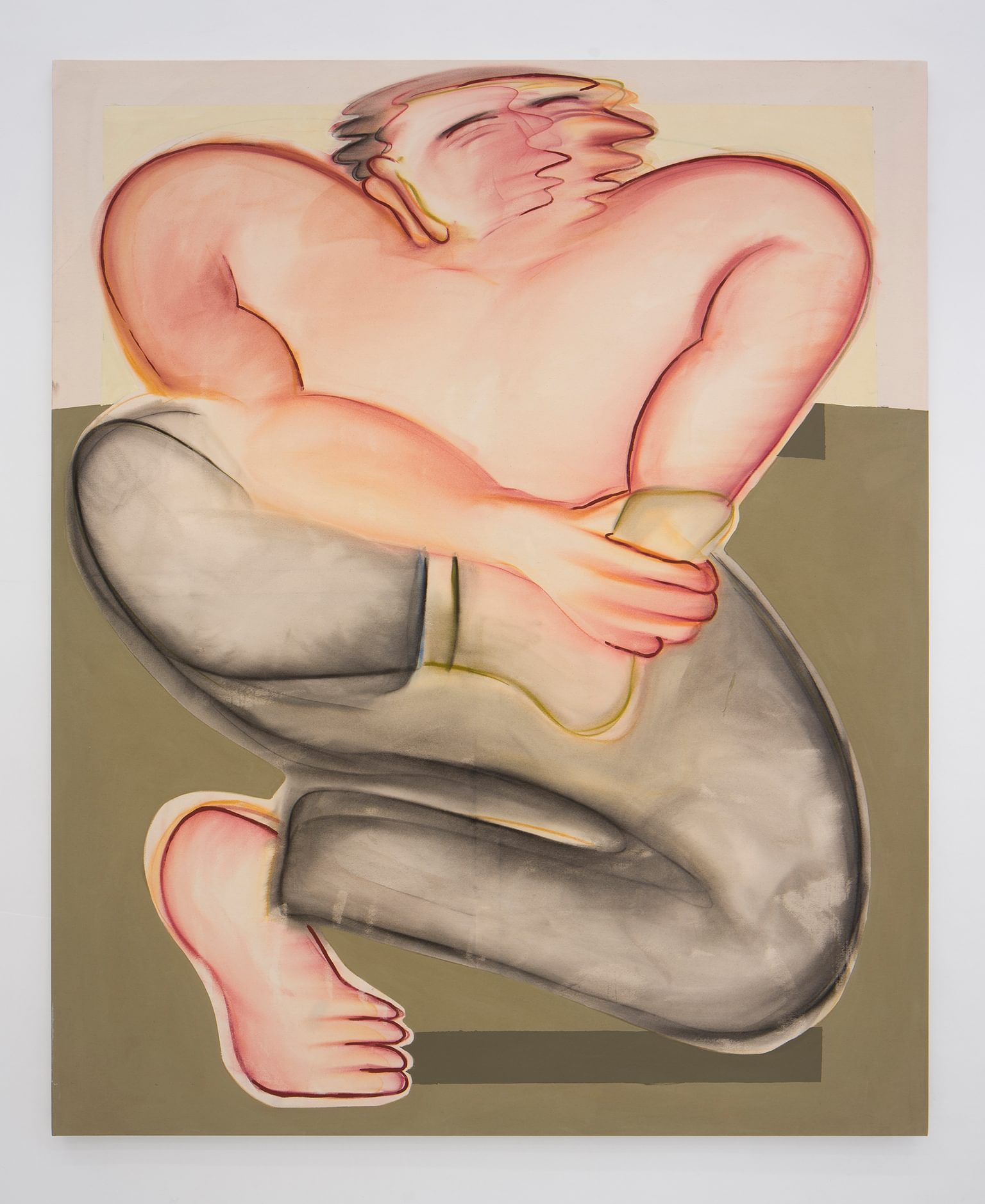

Anastasia Bay, A Song of Love (4), 2021, Acrylic and oil on canvas, 200 x 160 cm

Courtesy of the artist and NEVVEN

As an artist, I’ve often had to contend with a handful of repeating, cliché art terms like, ‘memory’, ‘identity’ and, ‘the body’. The body as ‘a site of trauma’. The body as this thing, that thing or the other. Finally, in July of 2021, after speaking to David Risley on the phone about writing this essay, the body at last became something I connected with art. [1] My body, the body in art, the body that makes art. Anyone suffering with acute pain will tell you that it’s hard to think of anything else. What’s been on my mind then is my body, and in the service of writing I managed to expand my thinking to include the bodies of others, and the body in general.

Paris born, Brussels based artist Anastasia Bay makes paintings with her body, and puts bodies in her paintings. In her paintings those bodies are big, and they exist inside big paintings, most larger than Bay herself. Bay paints, among other things, samurai and dancers. The figures are both faint and strong, occupying almost all the canvas, seemingly prepared to push left or right and break free of the frame. In Bay’s paintings fighting looks like dancing and dancing looks like fighting. In boxing, metaphors about dancing abound, and dancers often look like strong, potentially violent people.

Approximately sixty-four thousand years ago, a Neanderthal placed their hand against the wall of a Portuguese cave and stenciled it with sprayed pigment. Another Neanderthal saw the painting, liked it, and decided to do the same. Hundreds more followed, leaving behind the patterned explosion of self-identification named Cueva de las Manos, or ‘The Cave of the Hands’. As a very young child, I was taught to make art by placing my hand against a piece of paper and tracing it with pencil. This was an assertion, a sort of fingerprint. I was taught that day that art was a means to express myself. Literally, to express my selfhood.

“This is me! That’s my hand! I made this!”

[1] At the time, David was contending with the numerous crippling effects of a broken back. At the time, I was dealing with the numerous crippling effects of a herniated disc in my cervical spine.

Hands at the Cuevas de las Manos upon Río Pinturas

Mariano - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

I can’t count the times I’ve heard that ‘painting is dead’. But it won’t die. It can’t. Because to paint the figure is to scream “I’m alive!” This may sound corny, but it’s true. Artists, possibly more than most people, need others to acknowledge their existence. Painting — particularly figurative painting — has been classified dead so many times that it’s become a zombie, stalking art fairs and galleries with haunting relentlessness. Anastasia Bay’s paintings, rendered with soft assuredness, are emblematic of the medium’s immortality. Every artwork is an assertion of its maker’s existence. For hundreds of years the body in art served an almost singular function: to demonstrate the relationship between people on earth and God in heaven. Once people began to suspect the absence of God, portraits and self-portraits emerged. Amongst others, Francisco Goya engaged in mercantile realism, painting portraits of young girls available, at the right price, for marriage. Amongst others, Frans Hals created portraits of both the elite and the lumpen, illustrating class distinctions and pedigrees. Then, the tide of history washed onto the shores of the twentieth century and art became functionless, photography having assumed the role of reliable documentarian. Unencumbered by utility, anxiety attacked all artistic mediums, and inevitably, all artistic messages as well.

The history of modernity is the history of anxiety in art.

We live in anxious times. The Plague* is sweeping its virulent hand across the planet, correcting, if heartbreakingly so, our overpopulation problem. Fires, angry and determined, are consuming vast swaths of the earth, displacing untold numbers of increasingly poor and suffering people. Political divides, racism and paranoia are rampant. Loneliness and isolation are epidemic. Capitalism has become a grotesque caricature, exacerbating the gap between rich and poor. The police can’t be trusted, nor can the news, which is no longer news but propaganda. Everyone is lost online in an unmappable black forest of targeted advertising. My computer knows my next move long before I do. Evolution has been fast-tracked by gnarled hands contorted to type on phones, so that in fifty years we’ll have talons instead. Television has abandoned narrative in favor of spectacle, and movies are almost always about superheroes, as we unconsciously hope for their rescue.

I can’t count the times I’ve heard that ‘painting is dead’. But it won’t die. It can’t. Because to paint the figure is to scream 'I’m alive!'

Paul McCarthy, Santa Chocolate Shop, 1997, Performance, video, installation, color photographs

©Paul McCarthy. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Peder Lund.

Paul McCarthy, Tomato Head (Green Shirt), 1994, Fiberglass, urethane, rubber, metal, clothing (62 objects), 213,3x139,7x11,7cm

Photo by Douglas Parker

©Paul McCarthy. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Peder Lund.

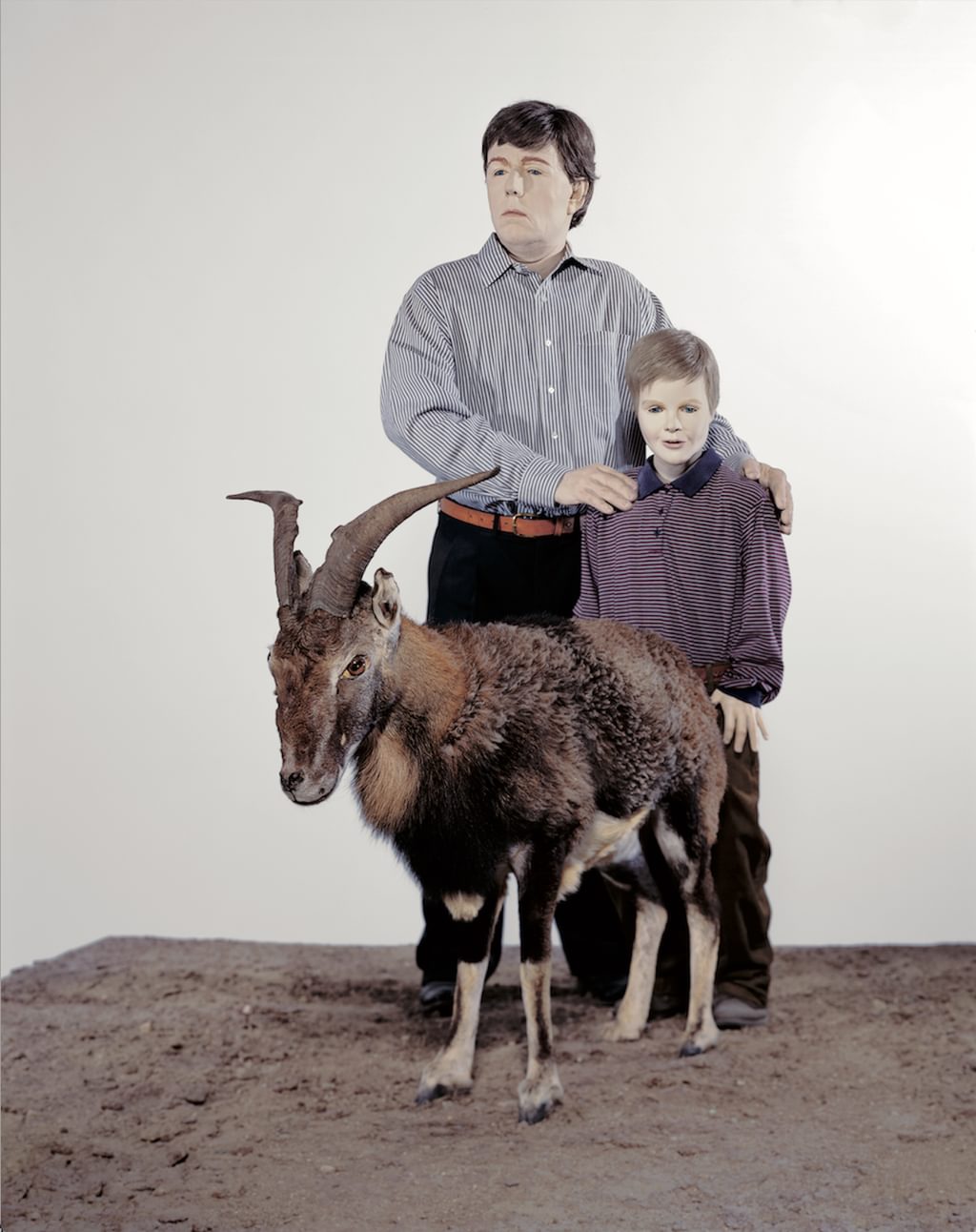

Los Angeles artist and conceptual art guru Paul McCarthy is acquainted with this level of anxiety, and his sculptures of bodies fairly ooze with embodied terror. Mr. Potato Head, stalwart member of the American toy community, looks panicked, staring at his nose and ear on the gallery floor, seemingly hopeful that some visitor will put his face back together (Tomato Head, (Green Shirt), 1994). Santa Claus is both scared and scary, his chocolate matted beard and face advertising a scatological Christmas (Santa Chocolate Shop, 1997). Snow White and her seven dwarves copulate with, and defecate on, each other, all the while smiling and whistling, unadulterated Americana (Inside Her Ordeal, WS, 2009). A creepy father encourages his even creepier son to penetrate a goat, the pair clad in middle American denim and corduroy (Cultural Gothic, 1992).

While they seem dissimilar, the above are not. All these works serve to represent virological America, beset by a deadly Plague. In Cultural Gothic, what the father knows, the child learns, as is true for the politics of vaccination and handwashing. Mr. Potato Head stands in for Joe America, the hapless victim of arch-capitalism, so distracted by his missing features he can’t remember what part goes where. The body as entertainment vessel becomes entertainment itself. Snow White, pimped out by Disney, has become the American Dream’s pornographic underbelly.

Paul McCarthy, Inside Her Ordeal, WS, 2009, oil stick, charcoal and collage on paper, 322,6 x 205,7 cm

Photo by Ron Amstutz. ©Paul McCarthy

Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Peder Lund

Paul McCarthy, Cultural Gothic, 1992, Wood, steel, fiberglass, wigs, clothing, compressor, pneumatic cylinders, PLC, urethane rubber, goat fur and horns, 244x244x244 cm

©Paul McCarthy. Courtesy the artist, Hauser & Wirth and Peder Lund.

Not since the Spanish Flu of 1918 has the global human body been so vulnerable. This is evident everywhere you look, including where you bought this journal, where it’s more than likely you were served by a cashier in a facemask that guarded their mouth against yours; two potential agents of death engaged in an economic transaction. While topical art can often later feel dated, all good art is eternally topical. Paul McCarthy’s sculptures make sense, right now, during the heart of The Plague, but they also would have made sense in 1918, and in any preceding or subsequent global contagion.

Last week I took my four-year-old niece to a museum. She ran towards a brightly colored painting by Alex Katz of two couples at a picnic.

“They’re standing too close together!” she said to me.

She was right, in a way. Around us all the visitors in the museum were spaced meters apart. At four-years-old, all her memories were informed by Plague etiquette. In Katz’s painting the figures were all side by side, flouting the rules we’ve all had to live under. I couldn’t think of what to tell her. Her understanding of reality wasn’t incorrect. The only thing I could do was to remind her that people in paintings aren’t real people, but then I thought of censorship, of The Origin of the World by Gustave Courbet, and became increasingly confused. Maybe she knew something I didn’t.

People who break their big toe will often say, “I didn’t realize how much I used my big toe before.” This is now true for the entire body, particularly the body that views art. In the past if we looked at art on a screen, it was because we had the option to do so, not because it was the only available way. But now, due to The Plague, some galleries have shuttered, and numerous art fairs are taking place online alone. This, like most things where the body is forced to compromise, comes at a cost.

Last week I took my four-year-old niece to a museum. She ran towards a brightly colored painting by Alex Katz of two couples at a picnic. “They’re standing too close together!” she said to me.

Gustave Courbet, L'Origine du monde ("The Origin of the World"), oil on canvas, 1866

Courtesy of Musée d'Orsay

In February of last year, I took my mother to see a Francis Bacon exhibition. I’d only seen a handful of his works in person before. I thought I loved Bacon’s paintings as much as possible, but was pleasantly surprised to find out that I could like them even more. His paintings smelled very good. I got to enjoy texture in his works that would be impossible to convey in a photograph. Viewed from the side, small wicks of dried paint stood away from the canvas. Orange met green in ways that made my eyes hurt. This, I thought, is the true beauty of art. An overwhelming sense of awe. I’ve been impressed by work I’ve seen online. I’ve enjoyed, been moved by, been envious of and amused by, artwork I’ve seen on a screen, but never before have I looked at art mediated by photography and pixels and felt truly awed. I mourn the loss of this rare feeling in our present situation.

This returns me to Anastasia Bay. I’ve never seen her paintings in real life. But I looked at her website and the websites of her galleries. I really like these paintings, I thought. I looked at the dimensions and saw that some were six, seven, eight feet tall. I thought, those are big paintings. But, even while understanding what eight feet looks like, it wasn’t until I saw a photograph of Bay next to one of her paintings that their size really registered. I saw how much larger than her her paintings sometimes were. That was when the size of her works truly clicked.

Anastasia Bay can really paint! I said in my head. Then, because I’ve hurt my own back attempting to work on large paintings, my next thought was to wonder if she ever hurt hers while painting.

This is the persistent focus that pain elicits. Everything becomes about pain, the potential for pain. A painting is beautiful, sure, but did it hurt to make it?

So, the old art cliché, the body. It persists. It’s true. It’s forever applicable. We depict bodies of art because we live inside of bodies. The body of the artist makes art for a viewer with a body. If not this Plague, another event. Forever the body. Birth and rebirth. The karmic wheel.

Anastasia Bay, A Song of Love, installation view, CHART 2021

Courtesy of the artist and NEVVEN

Brad Phillips is an artist and writer based in Toronto and Miami. New York Magazine called Essays & Fictions, his collection of short stories, one of “the most influential books of the decade.” He is represented by DeBoer Gallery in Los Angeles.

Anastasia Bay (Paris, 1988) graduated from the prestigious École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris (2012) and her recent exhibitions include Anna Zorina Gallery (New York, October 2021), Sorry We’re Closed (Brussels, 2021), Galerie Derouillon (Paris, 2021) and Spurs Gallery (Beijing, 2020). Bay lives and works in Brussels, Belgium.

Paul McCarthy (b. 1945, US) is among the most widely influential and important artists of his generation. Since the 1960s, McCarthy has worked within a broad range of artistic expressions, spanning media such as video, performance, painting, drawing, and sculpture. McCarthy is often associated with Wiener Actionism and its brutal and relentless expressions, which sought to attack conformism, conservatism, and the contentment of society. He challenges both his own and the audience's boundaries and invites us to view the ordinary with fresh eyes to discover how illusory and relative our conception of reality is.