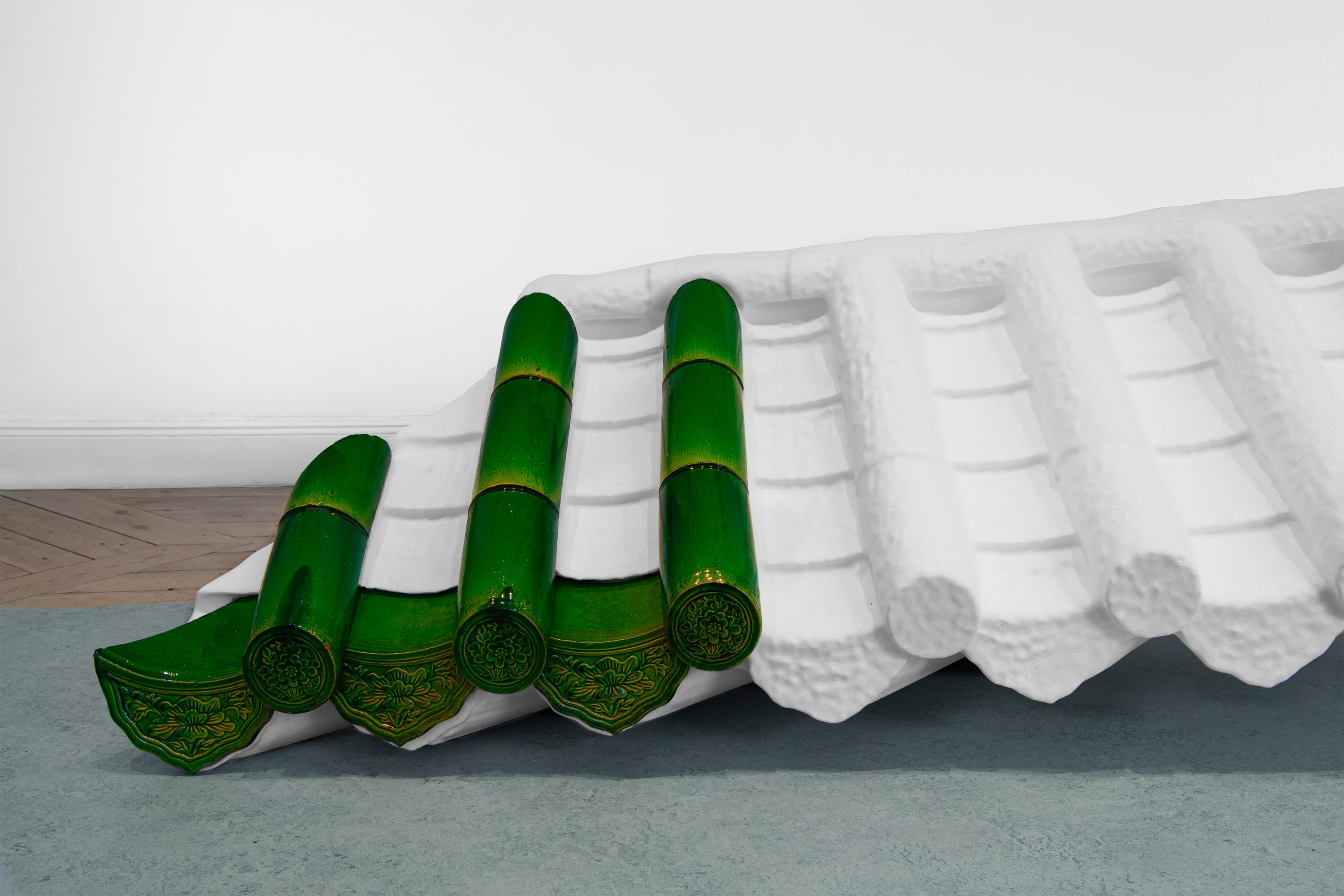

Lap-See Lam, Installation view, Bonniers Konsthall, 2018

Photo by Beata Cervin. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nordenhake

The metaphor of a ‘mother tongue’ refers to the utterance of a speaker in their native language—words belonging to the code of systems that verbalize reality practiced since birth. A ‘slip of the tongue’ (parapraxis) reveals a hidden desire. To speak in many of them (glossolalia) is an experience of religious ecstasy or delirium. If stolen by a cat, you are inexplicably silent. In expressions, the tongue is the muscle responsible for communicating symbols of understanding.

For Swedish artist Lap-See Lam (b. 1990) her lingua franca is articulated in images that interpret the aesthetic of a Cantonese diaspora in the context of her native Europe. In recent exhibitions, the emblem of the Chinese restaurant has been her subject. The evolution of Mother’s Tongue, Lam’s collaborative work with film director Wingyee Wu (b. Stockholm, 1976), was originally commissioned in 2017 and has developed in six iterations over the past four years including installations at the Moderna Museet Malmö (Sweden, 2018), Performa 19 (New York, 2019), and most recently Trondheim Kunstmuseum (Norway, 2021), among others. Initially developed as an interactive app [1], the work unfolds in three distinct fictional accounts—past (1978), present (2018), and future (2058)—over the course of a walking tour across disparate sites in Stockholm. The narrative is told through the voices of intergenerational women—grandmother, mother, daughter—against the backdrop of a virtual reality animation. Visited by spirits, like the three fates, the storytelling structure of Mother’s Tongue mirrors a type of mythic thinking born of Lam’s own history (her family owned and operated the Bamboo Garden in Stockholm) and extends toward a more encompassing vision of how remnants of alterity come to define culture.

[1] Commissioned by the non-profit public art association Mossutställningar, developed by Appster.

Lap-See Lam, Mother's Tongue, Installation view, 2018

Photo by Vigfús Birgirsson / Cycle & Art Festival. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nordenhake

As the monologues track, the screens of our smartphones pan across the ritual of rooms that constitute all restaurants (the hostess booth, dining room, pass through kitchen, inventory storage) alongside the specificity of an aesthetic marketed toward the illusion of transporting the Western customer to an elsewhere they expect reflects Chinese cuisine. Pagoda roof tiles indoors, horseshoe-backed chairs, red lacquer panels upon the walls, jade hued cloth napkins, casts of foo dog statuary—combinations of kitsch that exaggerate notions of place. Yet here, they are only pictured in partial view; composed entirely of 3D scans, the same device often used in forensics or archeology, we only see what the laser can touch as the artist moves through the spaces. The interiors are incomplete facsimiles of real locations throughout Stockholm; establishments such as New Peking City and Ming Garden, whose nomenclature is typical of the Chinese restaurant genre, elicits a type of fortification or paradise. Though recognizable, what we can see is equally defined by the gaps, glitches, and holes of what we cannot. While we stand still, our gaze involuntarily moves through the quarters as if we are acting witness to an underwater voyage, discovering either the remnants of a shipwreck or Atlantis, or a specter observing life on earth from another realm.

The double ghost nature of the work—adopting the visual language of haunting in order to point to the phantoms of history and culture that define the diaspora experience—dwells within its variations. Like language, the materiality of objects and locales that Mother’s Tongue pictures are often lost in translation. Or perhaps, they mutate. In Phantom Banquet (2019-2020), Lam’s recent solo exhibition at Galerie Nordenhake in Stockholm, a circular white clothed table is surrounded by a set of slipcovered chairs as if staged for a séance. Each participant of the work—the viewer that elects to sit—is adorned with a VR headset that enacts a scene of a young girl (you become her) who disappears through the void of a mirror into another dimension. When the work functions at full capacity, heads at the table stare out into space but face into the screen.

Lap-See Lam, Phantom Banquet, 2019-2020, Installation view at Galerie Nordenhake

Photo Carl Henrik Tillberg, courtesy the artist and Galerie Nordenhake

Lap-See Lam, Phantom Banquet, 2019-2020, Installation view at CHART 2021

Photo Niklas Vindelev

“Prophecy. As in true. As in Cassandra, speaking from the solitude of her cell. As in a woman’s voice. The future falls from her lips in the present, each thing exactly as it will happen, and it is her fate to never be believed.”

The Invention of Solitude, 1982

Lap-See Lam, Horizontal Landscape, Vertical Ghost (part 1), Installation view, 2019

Photo by Peter Hansen. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nordenhake

Lap-See Lam, Horizontal Landscape, Vertical Ghost (part 1), detail, 2019

Photo by Peter Hansen. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nordenhake

Returning to my home in Chicago after viewing the work at CHART in Copenhagen, I search my bookshelf for a copy of Paul Auster’s memoir The Invention of Solitude, published following the death of the author’s father. On its cover, there is a photograph: “There are several of him sitting around a table, each image shot from a different angle, so that at first you think it must be a group of several different men…and then, as you study the picture, you begin to realize that all these men are the same man…Each one is condemned to go on staring into space, as if under the gaze of others, but seeing nothing, never able to see anything. It is a picture of death, a portrait of an invisible man.” [2] I am reminded of one underlined passage, flipping through the pages I find: “Prophecy. As in true. As in Cassandra, speaking from the solitude of her cell. As in a woman’s voice. The future falls from her lips in the present, each thing exactly as it will happen, and it is her fate to never be believed.” [3] That Lam’s soothsayers are female narrators is significant. Each of them functions like a figure of Cassandra—the cursed goddess—heard, but unbelieved, they utter truths of what we know but refuse to listen to. “Parts of me are so displaced, that displacement has become my sense of being,” [4] says one woman (ghost of past). We hear the girl (ghost of present) called ‘banana kid’ by a member of her family followed by the subtitle: “Auntie explained that banana kids have yellow skin and a white heart.” [5] “Choose a language in the menu if your mother hasn’t taught you Cantonese,” says the future voice, “I hope you’ll want to listen to what I have to tell.” [6] Languages, like people, die too. The promise of the future remains that technology will advance enough that we can recover our mother’s tongue—just as easily as one restores the factory settings of a device.

Yet, it is the slippages of language and translation that Lam dramatizes throughout the dialogue of her works. The shadow cast by misinterpretation so familiar to first-generation children. “Mom with her Chinese and poor Swedish. Me with my Swedish and poor Chinese,” says the girl, an autobiographical avatar of the artist. Rimbaud, in his native French, writes in a purposefully incorrect grammar “Je est un autre,” (the proper conjugation would be je suis) and yet we comprehend the phrase more perfectly. Otherness always articulates, and therefore exists as, an improper nature. The error enacts a concrete poetry. In the context of Lam’s mother tongue, an English title that adopts a gender-specific term for a universal concept in the possessive, we are reminded that there is no such thing as the ‘other’ inside the womb.

[2] Paul Auster, The Invention of Solitude. Penguin, 1982. (31)

[3] Paul Auster, The Invention of Solitude. (127)

[4] Lap-See Lam and Wingyee Wu, Mother’s Tongue. App Store, developed 2018. From the chapter “Miss China.”

[5] Lap-See Lam and Wingyee Wu, Mother’s Tongue. From the chapter “Peach Tongue.”

[6] Lap-See Lam and Wingyee Wu, Mother’s Tongue. “Cyborg World.”

Lap-See Lam, Phantom Banquet at Galerie Nordenhake, installation view, 2020

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Nordenhake

Stephanie Cristello is a contemporary art critic, curator, and author based in Chicago, IL. Her work focuses on artists who critically engage with the image and its role in visual culture. Through the lens of Classics and mythology, her diachronic writing practice concentrates on the intersection of ancient narratives and conceptual practice post-1960. Her research is specifically motivated by contemporary works that interrogate how language, text, and the use of poetic devices influence and shape the cultural and historical structures that surround us. She has worked internationally across a variety of platforms, including exhibitions, panels and symposia, editorial and publishing, and has contributed to numerous exhibition catalogues nationally and internationally.

Lap-See Lam (b. 1990), Stockholm. She has a major upcoming solo exhibition at Bonniers Konsthall opening 9th February 2022. Solo exhibitions include Skellefteå Konsthall, Skellefteå (2019); Moderna Museet Malmö (2018–2019); and Bonniers Konsthall, Stockholm (2018). Lam is a recipient of the Maria Bonnier Dahlin Foundation Grant (2017).