AYE-AYE is a new initiative that has been set up as a parasitic exhibition space, attaching itself to Overgaden and situated upstairs in the former office of director Rhea Dall. AYE-AYE taps into the resources of the larger organisation, from the building to its utilities, whilst putting forward an independent programme of shows. The conversations these exhibitions foster vary in nature, and the juxtapositions they build explore and expand upon the idea of objectness in art and the objecthood of aesthetic, critical and emotional stimuli. This interview explores founders Nina Beier and Simon Dybbroe Møller’s motivation for starting AYE-AYE and the new ideas that they are promoting within Copenhagen’s artistic environment and beyond.

Nina Beier and Simon Dybbroe Møller, founders of AYE-AYE

AYE-AYE #1 Geology, featuring the work Soil for Scoresbysund, installation view, 2021

Photo by AYE-AYE

How did you start AYE-AYE?

The project grew out of long discussions about our own individual practices and exhibition-making experiments. We have a mutual interest in found objects. We both question how subtle contextual changes can entirely alter an object’s presence. We wanted to take these discussions to a different place, outside of our respective practices.

So in many ways, AYE-AYE is an attempt at conducting fundamental research into how to engage with objects and how to make exhibitions. At AYE-AYE we employ one of the most basic exhibition principles that is arranging multiple objects in relation to each other, juxtapositioning things, or in other words combining them. If you think about it, even the display of a singular artwork is an arrangement of one object inside another. AYE-AYE is an attempt at creating a simple structure for thinking about all of this.

Can you talk about your parasitic condition? Does that allow you to explore a non-institutional constellation within the framework of an institution?

There is a pragmatic reason for the institutional setting. We will regularly borrow objects from established institutions, and they necessitate displaying in an art gallery equipped with security systems, alarms, and so on. At the same time, we’re aiming for some kind of institutional experimentation, that is, we try to place AYE-AYE somewhere in the exhibition landscape that feels uninhabited.

AYE-AYE #2 Mortality, detail, 2021

Photo by AYE-AYE

AYE-AYE #2 Mortality, installation view, 2021

Photo by AYE-AYE

Can you talk about the shows you have been putting together so far?

Our first exhibition was titled "AYE-AYE #1 Geology, featuring the work Soil for Scoresbysund" by the Greenlandic-Danish artist Pia Arke placed in conjunction with a collection of “meat stones” on loan from a collector in Germany.

Pia Arke’s maternal grandparents were among a small group of Inuit families who were displaced to Scoresbysund as part of a scheme to maintain the sovereignty of the colony of Denmark. Pia Arke’s piece is made out of a collection of used coffee grounds that have been packed into filters and saved to be scattered as compost, in reference to the method by which her grandparents tried to create more soil in the barren East Greenland outpost where they lived. The thing is that coffee was introduced to the Greenlanders by the Danes. Some people speculate that it was introduced to create habits, needs and dependency, to create the foundations for trade.

We paired this piece with a collection of sedimentary rocks which look like pork or beef. In China, Japan and Korea these types of “meat stones” are highly valued by collectors and prices vary according to their size and strength of resemblance. The stones in the show were sourced from a German meat stone enthusiast.

Our second exhibition was titled AYE-AYE #2 Mortality, and displayed Napoleon’s mother’s death mask that we borrowed from Thorvaldsen’s Museum and a toy weapon collection acquired from a 10 year old child during a serendipitous encounter on an online platform.

The mould of a death mask is made by direct contact with the deceased person’s face; so that the cast from the mould is at one remove. This particular cast, which was taken by the Danish sculptor Thorvaldsen, has two pieces of Laetizia Bonaparte’s eyebrows in it. One could say the copy consumed some of the original.

We decided to organise the toy weapons exactly as they were being offered via the online auction. Laying on the floor of exhibition space, these scaled down representations seemed to offer an incomplete yet carefully composed image of the lineage of weaponry. We had a horse bow, several semi-automatic handguns, a sabre, broadswords, daggers, a baseball bat and a battle axe.

"When you reduce the exhibition format to the extent we are doing, whilst also stripping away all the time consuming practicalities involved in making large-scale exhibitions, it probably increases focus and generates a more unobstructed commentary on the very essence of meetings between objects."

What are the limitations of programming in such a small space and what are thefreedoms you have?

When you reduce the exhibition format to the extent we are doing, whilst also stripping away all the time consuming practicalities involved in making large-scale exhibitions, it probably increases focus and generates a more unobstructed commentary on the very essence of meetings between objects. Enabling ourselves and the audience to look at things in depth, as if they are viewing them under a microscope.

How did you decide on the methodology of the exhibitions i.e. juxtaposing two works by different makers into a conversation?

It’s not because we’re only interested in binary opposition, and obviously the fact that there are only these two things in the space, and that they are colliding with each other, is anxiety-provoking. But it feels really exciting to allow things to hit each other really hard as carriers of meaning. The objects on display are rarely immediately related, nor are they opposites. It is all about paratactic independence.

You not only create these dual-conversations, but also multiply them into further dialogues. That is to say, inviting an artist to make a film of the exhibition that is

joined by the sound tracks which you produce for the shows in order to form the documentation of the exhibition is rather experimental as well as multi-vocal. Can you please outline your motivations and desires for such an approach?

The question which we started with is whether the show is the final outcome which is then documented, or if the show is a film set and the film is the final outcome. And the answer must be both. It makes sense as the voice-over offers itself to both formats and makes a bridge between the two. In order to give the film component its own authority, we are working with different artists and filmmakers to make these independent films capturing the shows. John Skoog and Maria von Hausswolff made the first two films and Asta Lynge and Jakob Ohrt are making the next one.

AYE-AYE #1 Geology, featuring the work Soil for Scoresbysund, installation view, 2021

Photo by AYE-AYE

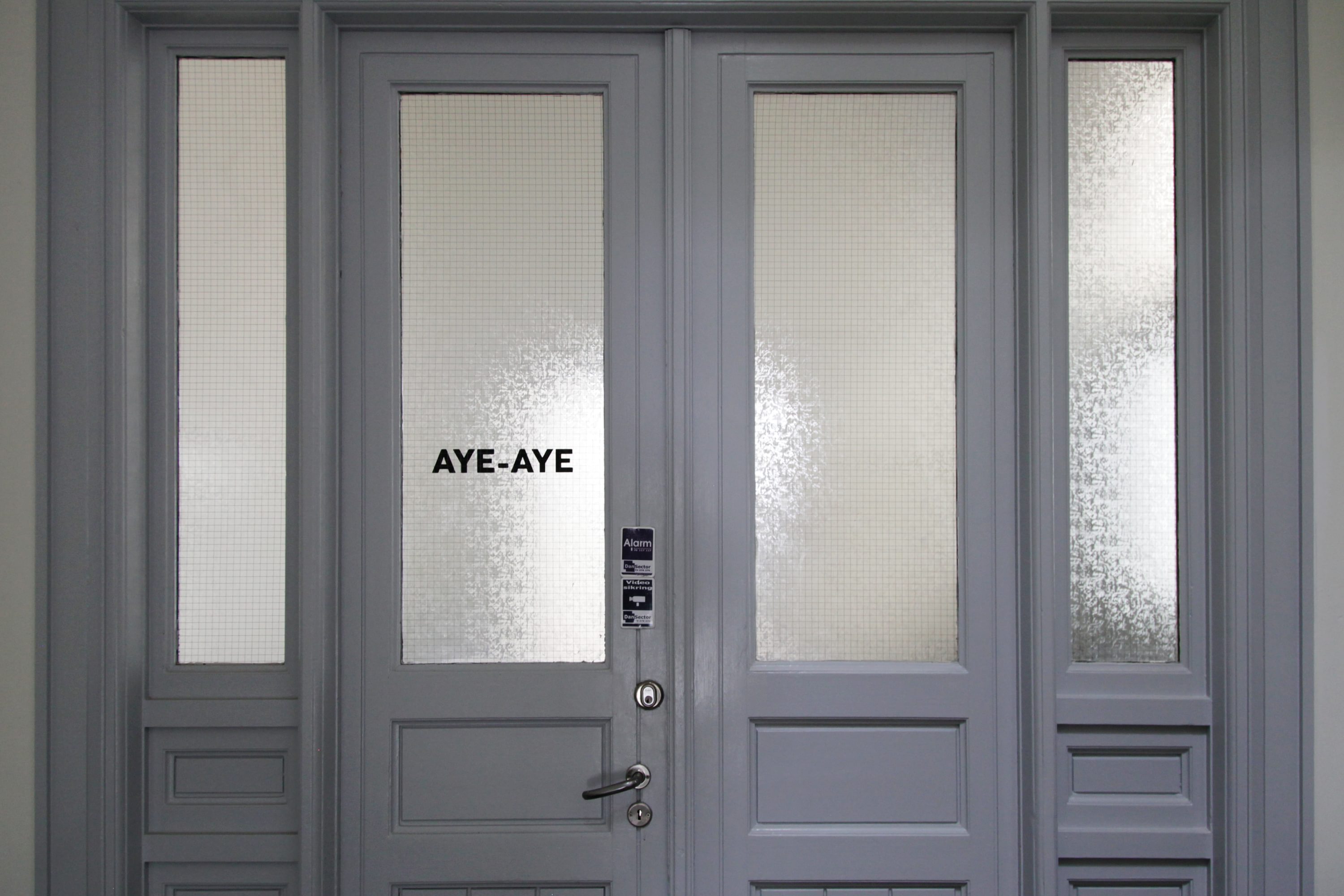

AYE-AYE, 2021

Photo by AYE-AYE

Can you talk about agility and spontaneity in regards to programming at Aye-Aye? Do you think of this as a counter-constructive position to today’s large scale art institutions and museums?

The small scale of our operation makes it possible to tread more lightly, but the formality surrounding institutional loans still keeps us in quite an un-spontaneous place.

How do you envision your contribution to the ever expanding parameters of cultural production?

AYE-AYE is a machine for dealing with the flood of images around us. By pairing objects and arranging them in a space we join in the game of analogies, question it, mess with it. Aren’t we currently living in a reality where cultural production is basically about sampling, taking things and putting them together? Maybe AYE-AYE is some kind of compressed culmination of this tendency, but in contrast to the mainstream, it is a place where the backstory is brought forth and amplified, instead of being erased.

Fatoş Üstek is an independent curator and writer, based in London. Ustek acts as editorial advisor and contributing editor to Extra Extra Magazine, board member of Urbane Kunste Ruhr, Germany; advisory panel for Jan van Eyck Academie, Netherlands. She was jury member for Turner Prize Bursaries 2020, Arts Foundation Futures Award 2021, Scotland in Venice 2022, Dutch Pavilion 2022, and acted as an external member of the acquisitions committee for the Arts Council Collection (2018-2020). She was Director of Liverpool Biennial, Director and Chief Curator at Roberts Art Institute (formerly David Roberts Art Foundation). She is the curator of Do Ho Suh’s largest UK commission (2018-2020).