Jesper Fabricius is a visual artist and co-founder of Space Poetry: One of the largest and oldest publishers of artist books in Denmark. Since 1980, Space Poetry has been promoting a playful and experimental approach towards book publishing and is responsible for producing important early publications by Tal R as well as the iconic art magazine Pist Protta, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. In recent years, Fabricius’ work with Space Poetry has been the focus of exhibitions at such institutions as: ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Kunsthal Charlottenborg and Design Museum Denmark. In the following interview, I sat down with Fabricius to discuss the formation of Space Poetry and the changing landscape of independent artist publishing over the past four decades.

Jesper Fabricius photographed in his studio.

Photo: Oscar Gilbert.

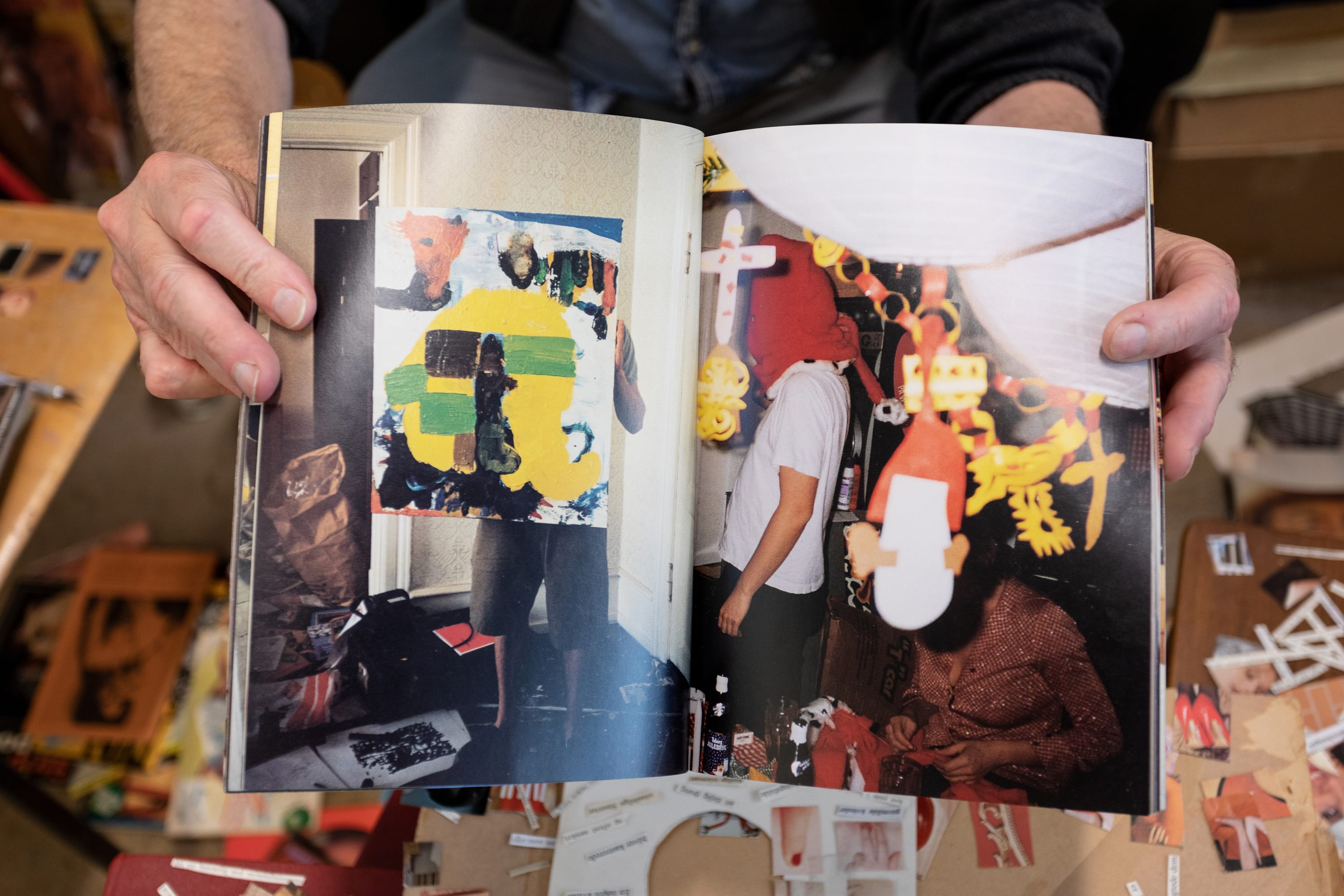

Everybody Please Go Home by Tal R. Space Poetry, 1997. Designer: Jesper Fabricius.

Photo: Oscar Gilbert.

I have read that at the beginning, you were part of an artist collective of sorts that was responsible for producing Space Poetry and Pist Protta, could I ask you to tell me about how the publishing project started?

Yes, that’s right, we were a few people. Quite young and actually we started by having an art exhibition in a town where a lot of us came from named Rudkøbing on Langeland in 1979. After that we had some photos from this exhibition and by then we had seen a lot of these smart new catalogues or artist books. I think I saw some Swedish ones, maybe some from Moderna Museet. I think they were mostly from museums because they had the cash. We thought we could do something similar with our photos and then of course we could also put drawings and poems in; it would be like a room for putting things in. The first thing we published was called “Kontainer” because it was a container for all this artistic stuff.

Where did the name 'Space Poetry' come from?

The name actually came from this exhibition on Langeland. At that exhibition we had this guy we had invited, who lived in Christiania. He was quite a bit older than us. He was English and a drug addict and very gentleman-like but also very wild. And some of the days, we had this like electric piano organ and he sat outside the exhibition playing it and reciting words. He called this activity “space poetry”.

Actually I think he scared a lot of people away, from the exhibition, but anyway it was also quite fun. One winter later we went to visit him in Christiania, and he was away, but later we found out from a girl he was living with that he had killed himself. So when we found that out, we thought this project could be called 'Space Poetry,' after his performance. So it’s a tribute to Roger.

"[...] The biggest difference was that the exhibition is in one place, but the book can be in many places; you can transport it... People wouldn’t come to us to see an exhibition because we were too far away and that was one of the reasons we thought we should start making some publications."

Spread from Kontainer, published by Space Poetry 1980.

Photo: Oscar Gilbert.

Was it difficult to find somewhere to produce the early publications?

We went to this printer "Eks-skolens Trykkeri" who we noticed were printing things for artists. It was an offset printers founded by the artist group Eks-skolen [“The Ex-School”], which included the likes of Bjørn Nørgaard, Per Kirkeby, Erik Hagens and a lot of artists who were very famous in Denmark, even at that point. So we thought “Ah, this could be the right place to go”, because they knew about artists. It was a very good experience, they had great ideas about formatting. The only bad thing was the price.

What were the biggest changes for you working with a print publication format as opposed to exhibitions?

The biggest difference was that the exhibition is in one place, but the book can be in many places; you can transport it. One of the guys from Space Poetry moved to Copenhagen quite early, but the rest of us were staying in a very small house, far out in the countryside in Northern Jutland. People wouldn’t come to us to see an exhibition because we were too far away and that was one of the reasons we thought we should start making some publications.

"The most important thing has been to travel, because when you travel you meet people outside of where you are coming from... It’s also about seeing how other people do things and learning by seeing what you are up against."

How did your eventual move to Copenhagen change the publications you were producing?

We had been working consistently before we moved to Copenhagen and continued afterwards, so in that way it was not like one big change. The change was that it became easier to get in contact with other artists.

We had found out that other artists were interested in the publication and interested in contributing, for example. It was not something that we did really think of in the beginning. But then they would send us letters asking to contribute something and we would realise, oh someone read that! That was fantastic.

What was your awareness of other independent publishers like as you entered this larger artistic community?

There were definitely other people working with publications. It was not like we were totally on our own, but from what I remember there were not so many people doing this in the beginning. In the 80s I mean. And then of course later there were more people doing it, it started growing in the 90s.

As it grew you could also start doing some things that were quite fun. We started working with a book printer who would help us make publications with coloured paper edges and different cut-out techniques. We were mostly still using offset printing but started to also work with more digital tools that made text-wrapping for example much easier.

In the 90s there were lots of groups who were making magazines and then all of sudden their next issue would come out on a disk or something, but you can’t read that issue anymore now because of the tools, they change so quickly.

Why has it been important for you to continue working with paper and printed publications?

When you have something on paper, it’s like it’s fixed. Of course it will disappear, because paper might only last for 100 years or something, but it has a physical presence and a heft. It is both a traditional and historical thing and it is much more like a thing you have really done than with images on the internet for example. And of course you have done all of this other stuff that is on the internet, but you have no idea where any of that material actually is. The benefit with paper is that you can physically handle it with your hands.

Jesper Fabricius studio view.

Photo: Oscar Gilbert.

Jesper Fabricius studio view.

Photo: Oscar Gilbert.

What has the process of international exchange been like for Space Poetry, and how have art book fairs helped to facilitate that?

The most important thing has been to travel, because when you travel you meet people outside of where you are coming from. You might go to a place just for fun but then you also sometimes meet people at the same time and maybe you will go back to them if you think you have something in common.

We did the first two Printed Matter book fairs and we have been back for later ones since. It was never really about the sales, you get out and you see other towns and you meet people who are also working with the same stuff as you, and maybe you can connect with them.

It’s also about seeing how other people do things and learning by seeing what you are up against. It pushes you to try something different because you never want to turn up with very bad stuff compared to the other people there.

What about more locally, do you feel a particular affinity with other publishers in the city or in the Nordic region more generally?

I think there are a lot of really good publishers, both here in Denmark and elsewhere. Here in Denmark there are a lot that I really like and think that they’re doing fantastic things. Like Asterisk, like Emancipa(t/ss)ionsfrugten, like Cult Pump. They are all doing things that are quite different to us, sometimes very playful, sometimes very strange, but I think it’s fantastic.

Finally, do you have any general rules for what makes a good artist book?

A good artist book is one that’s not too heavy.

Jesper Fabricius studio view.

Photo: Oscar Gilbert.

Oscar Gilbert is a gallerist and writer based in Copenhagen, Denmark. In 2019 he founded the contemporary art gallery OTP Copenhagen.