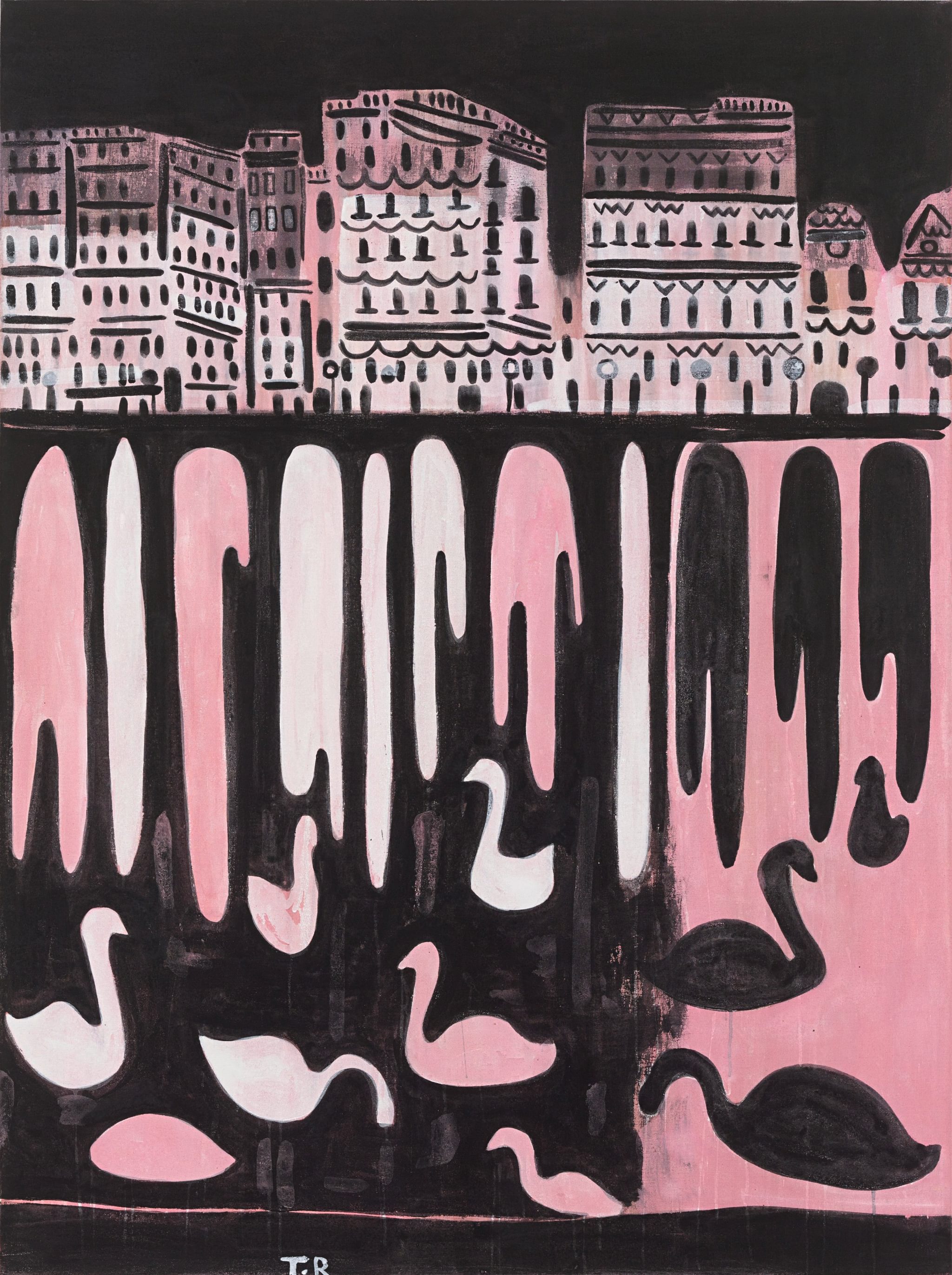

Mamma Andersson, Svanedamm [Swan Pond] (2016). Oil and acrylic on panel, 122 x 149,5 cm.

Courtesy of the artist, Galleri Magnus Karlsson & Galleri Bo Bjerggaard

“And how can body, laid in that white rush / But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?” [1] — W.B. Yeats, Leda and the Swan, 1924

Sometimes strangers make good lovers. Feelings extend past seduction, communion ensues. Bodies get lost, consciousness forgets them, and psyches blend in the dark behind the flutter of closed eyelids. Intuition supplants thought—both surrender to the deception of understanding one another. Of suddenly gaining impossible access to a well of experiences that have long defined a familiar pattern of seclusion between two foreign selves.

The innocence of such counterfeit intimacy becomes unsteady if the terms for romance turn out to be false. A sleight of facts, a purposeful omission, a breach beyond the necessary lacuna required to maintain the thrill of mystery. A violation. For example:

Leda, bathing in the river, lays her eyes upon a swan (Zeus in disguise)—he charms, she acquiesces, the distance between them closes, and she is raped.

As one of the most prevalent tropes in the history of painting and poetry (nearly all creatures of male fantasy), the realm of symbols that compose the countless interpretations of the Greek myth Leda and the Swan from antiquity to the present is embedded within Western language, representation, and culture. In art, the rape is often depicted as a seduction—as love in place of menace. Tableaux of pastoral tenderness, her neck bending down to meet the swan’s beak, a languid reclining embrace. Poetry possesses more precision among the Romantics; W.B. Yeats writes of “a sudden blow” and Leda’s “terrified vague fingers,” [2] Mallarmé makes use of the words for ‘swan’ and ‘sign’ as homonyms in French (le cygne, le signe), [3] Rilke equates the feathers of the swan to writing the instrument of a plume, [4] and the female imagist H.D. is the only to rewrite a peaceful Leda that is entranced rather than assaulted by an otherworldly bird. [5]

[1] W.B. Yeats, “Leda and the Swan.” The Cat and the Moon and Certain Poems. Dublin: Cuala, 1924.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Stéphane Mallarmé, “Le vierge, le vivace, et le bel aujourd’hui.” Poésies. Paris: Gallimard, 1945.

[4] Rainer Maria Rilke, “Leda.” Neue Gedichte, 1908.

[5] HD, Collected Poems, 1912–1944. New York: New Directions, 1983.

Antonio da Correggio, Leda and the Swan, c. 1530. Oil on canvas, 156,2 × 217,5 cm.

Gemäldegalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Peter Paul Rubens, Leda et le cygne, 1601. Oil on panel, 64,5 x 80,5.

Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

The genre of the swan, as both a subject and a perpetrator of our natural and social environment, engages with narratives surrounding desire and power. Swans signal a curse, a synonymous icon of beauty and danger—between the exquisite and the wicked, the elegant and the ominous—within our contemporary lexicon. The ethos of the #metoo movement discloses that everyone either knows or has been Leda. A predatory God, like any manipulative authority, takes from those what is not given. Centuries later, we see a camera that traces the body of Billie Eilish wrapped by a serpent on a mountain face amid a desert landscape in the viral music video for “Your Power” as she sings “and you swear you didn’t know, you said you thought she was your age.” [6] In ancient myth and contemporary culture alike, the apparition of a bestial stand-in for abuse is perhaps easier to digest. The refrain how could you? echoes against the obvious: the culture of rape is trained and accepted. As Yeats writes in his 1924 poem, one of the few male artistic visions that privilege Leda’s perspective, “And how can body, laid in that white rush / But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?” [7] In the metaphor of the ‘white rush,’ the poet envisions the potential of transforming transgression into self-possession, into inspiration—into art.

[6] Billie Eilish, “Your Power.” From the album Happier Than Ever, 2021.

[7] Yeats, “Leda and the Swan.”

Still from the music video for “Your Power.” Billie Eilish, Happier Than Ever, 2021.

In the field of painting and contemporary art, the depiction of swans inevitably imports this history. In the work of Mamma Andersson and Tal R, through their collaborative two-part exhibition Svanesang (Swan Song) that took place in 2016 at Gallery Magnus Karlsson (Stockholm, Sweden) and Galleri Bo Bjerggaard (Copenhagen, Denmark), we see a response to the Leda and the Swan genre pictured in a rare act of empathy. Conceived as exchange of source material while the two artists were relative strangers to one another, their image-based communications—which included photographs of swanneries, lonely figures on bridges, skeletons, and patients in insane asylums, among other subjects—provided a conceptual structure that incepted the path of a thought before becomes an artwork. The collection of paintings and drawings that composed the parallel exhibitions imagined the artists’ shared motifs in glinting patterns; at times, Andersson and Tal R’s compositions functioned as mirrors whose reflections were defined by mere differences in style, while at others they depart, dissolving into the distinct subjectivities of each artist. The ebb and flow of the images—a result of common cues revolving around Romantic themes: equal measures love, death, and madness—find closeness via a necessary intrusion, where the staged raid of each other’s practice results in creation instead of conquest. Like good lovers, their images envelop and press into the other in scenes that are better together than apart. In finding this equivalence, each painting holds the ‘strange heart’ that beats.

Andersson and Tal R’s twin visions present a tacit agreement: you can steal from me, and I can take from you. Thieves are not always badly behaved.

In two works featured as part of the Stockholm chapter, Andersson’s eponymous Swan Song (2015) and Tal R’s The Rosa Bend (2016), similarly scaled canvases feature a hunched over woman. For Andersson, the figure is closely cropped as if being held tightly within the frame. Constricted and contained, her head bows toward the knees of her white frock in a gesture of either penance or contemplation. The focus remains on her inwardness, a searching, against a nondescript background bathed in a deadened palette of burnt umber and ultramarine blue. Tal R’s composition allows for more space; the harshly outlined boundaries of the rose-hued woman tilts her head toward us in semi-profile. While retaining a certain flatness of perspective, her environment is markedly more architectural, abstractions of place unfold around her. Seated upon a green ladder-like object in place of Andersson’s wooden bench, a carpet bearing a floral pattern that resembled downward pointing arrows mimics the implied motion of her gaze. In both, the unidentified woman recalls Albrecht Dürer’s iconic engraving Melencolia I (1514), a representation of the manic-depressive disposition said to result from the inertia of artistic genius. [8] In both Andersson and Tal R’s representations of the bent muse—a found image Andersson sourced from the archives of an insane asylum—the allusion to either introspection or a descent into madness serves as a primer for the vanitas approached throughout their past and future collaborations.

Mamma Andersson, Svanesang [Swan Song], 2016. Oil and acrylic on panel, 124.5 x 100 cm.

Courtesy of the artist, Galleri Magnus Karlsson & Galleri Bo Bjerggaard

Tal R, The Rosa Bend (2016). Pigment and rabbit skin glue on canvas, 172 x 137 cm.

Courtesy of the artist, Galleri Magnus Karlsson & Galleri Bo Bjerggaard

While they are mute throughout the whole of their lives, swans sing before they die. A suspension between here (our world) and there (perhaps nothing), their music marks a gateway between the end of life and the beginning of death. In Andersson and Tal R’s paintings, the mortal lyricism of swans is uttered without sound. Giorgio Agamben writes, “Painting is the making of mute poetry, the silencing of the word. This is not simply because in painting poetry ceases to speak, but because in painting the word and its silence are visible.” [9] Throughout the artists’ portrayals of swanneries, the birds’ attribute of muteness is broken. The paintings appear to sing to us. A brush pulls across the canvas like the bow of a violin. Washes of pigment bleed from the touch of a pianissimo finger upon an ivory key. Staccato marks punctuate a forest in depths of rhythm. Throughout their images, we see a type of ballad that operates through call and response—a duet in harmony. In Tal R’s Svaner om natten (Swans at night) (2016), swaths of pink, white, and black delineate the nocturne composition. The shadows of buildings upon a canal, or perhaps the swans, are cast onto the water like fragments of illegible text—a secret poem. We see light through the source of a harsh evening sun as it passes into twilight, whereas in Andersson’s Svandamm (Swan Pond) (2016) a characteristic earthen softness shrouds the landscape. Beyond the silhouette of a black bough, the snowy plumage of five birds appears to glow against peach ripples inscribed upon the surface of an otherwise still mint blue stream.

Amid the two exhibitions, and in their respective practices since, permutations of swans arise either alone or in regatta. Between the exacting and the ethereal, a crescendo and a whisper, Andersson and Tal R’s picturesque and somber paintings articulate the double facet of the swan song. Upon the metaphor born of the phenomenon, which often translates to signify a finale, the artists’ transpose the very language of seriality that gives way to genre painting as a substitute for a closing act. Of this fantasy of return, or regeneration, Andersson recollects on the relationship between sound and birds within the context of her studio, “Nature is very loud. I think about the birds in our summer house [with artist and husband Jockum Nordström]—and every year we see the same birds making their nests and feeding their children. We hear the special sound of their wings. Of course, if I take this idea one step further, it is clear they are not the same birds. They are new birds; we just don’t see them dying.” [10] She continues, “it is very much the same as people. We are all passengers in time: here for eating, fucking, crying over the various losses we have, etc. As I get older, my conception of death no longer relates to others—it is about me now.” [11]

[8] Melancholy, one of the original four humors, was first developed in Ancient Greek medicinal practice and was said to be related to an imbalance of the spleen as well as guided by the planet Saturn (Kronos, God of Time).

[9] Giorgio Agamben, “Image and Silence,” Diacritics 40, no. 2, (Summer 2012): 94–98. 96.

[10] Mamma Andersson and Tal R, public talk at Kunsthal Charlottenborg as part of CHART Art Fair. Moderated by the author, Stephanie Cristello, August 29, 2021.

[11] Andersson and Tal R, CHART, August 29, 2021.

Tal R, Svaner om natten [Swans at night] (2016). Pigment and rabbit skin glue on canvas, 172 cm x 128 cm.

Courtesy of the artist, Galleri Magnus Karlsson & Galleri Bo Bjerggaard

Mamma Andersson, Svanedamm [Swan Pond] (2016). Oil and acrylic on panel, 122 x 149.5 cm.

Courtesy of the artist, Galleri Magnus Karlsson & Galleri Bo Bjerggaard

“[...] it is very much the same as people. We are all passengers in time: here for eating, fucking, crying over the various losses we have, etc. As I get older, my conception of death no longer relates to others—it is about me now.”

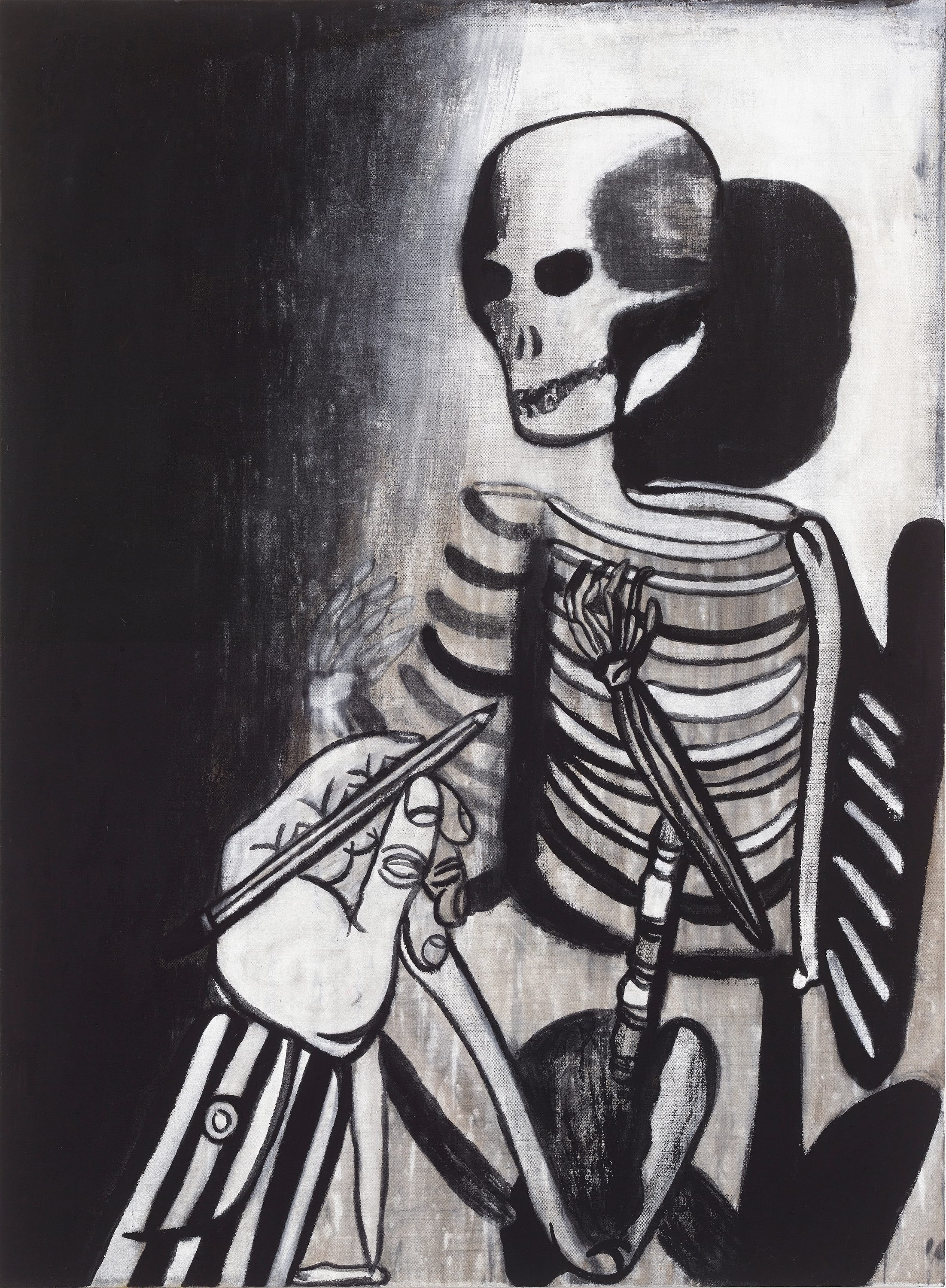

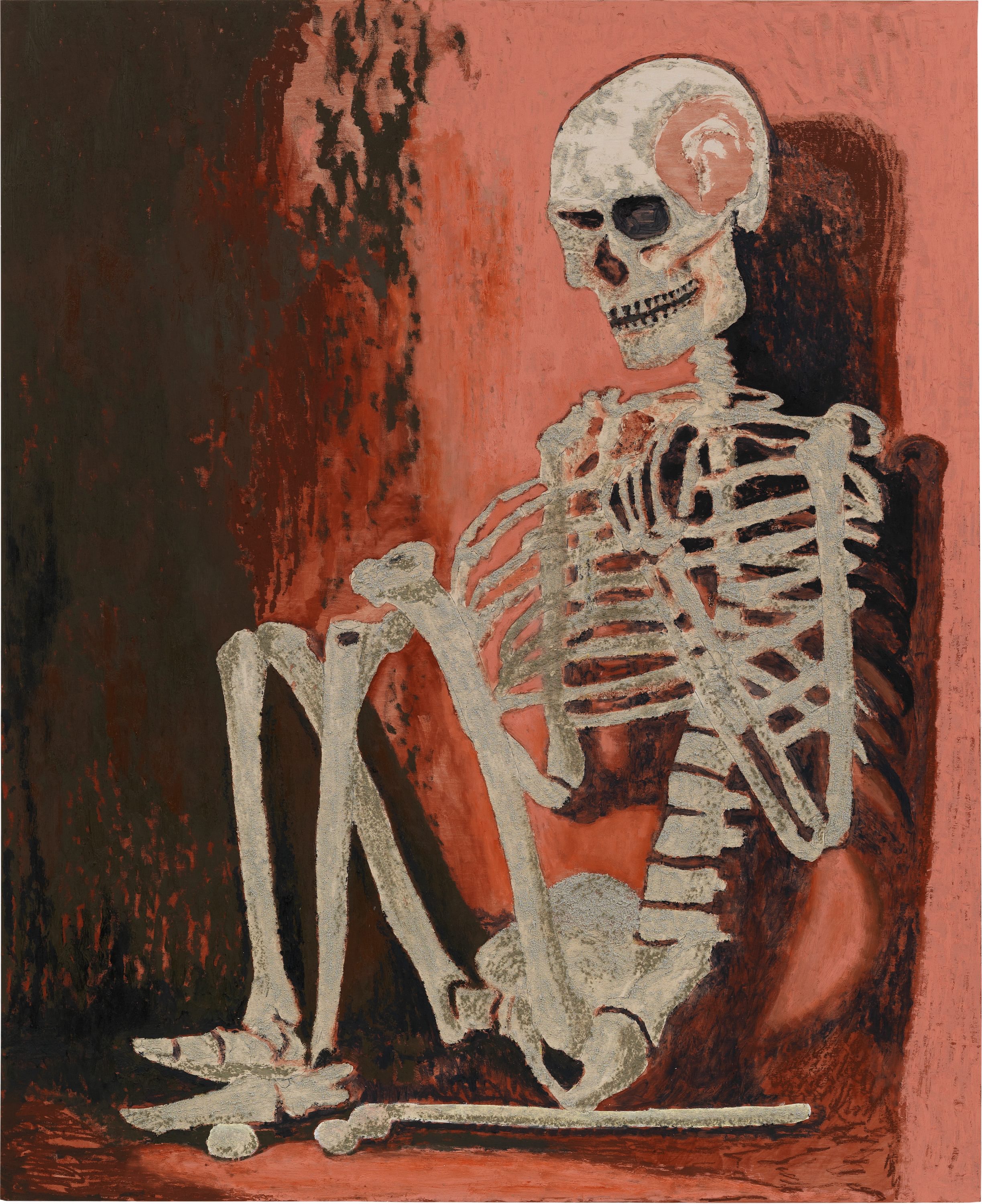

Concerning death, the motif of the skeleton appears alongside the mad woman and swans as one of the artists’ key collaborative subjects. In At tegne skelet (She draws the skeleton) (2016) by Tal R, a black and white painting disguised as a drawing, a pencil in a hand reaches up from the lower edge of the canvas, sketching its own demise. “Skeletons are a very banal thing,” says the artist, “we all have them inside of us.” [12] In preparation for the artists’ next collaborative exhibition, the representation of death pivots from the image of skeletons to the landscapes of Swedish artist C.F. Hill (1849–1911). Hill, who Andersson describes as “two artists in the same person,” [13] serves as an allegory for the death of identity resulting from severe illness. In the case of Hill’s short life, following his early years as a Classically trained painter he faced a split within his work after being hospitalized for severe psychosis, paranoia, and delusions at the age of twenty-eight. A death of the painter he once was, and a death of reality. In working with the largest collection of Hill’s drawings over the past year, which belongs to the archives of the Malmö Art Museum (with over 2,600 works), Tal R notes of the next chapter of collaboration with Andersson, “we have decided to put someone else between us.” [14]

The forthcoming exhibition—which will take place in three venues in 2022–23 across Sweden, Denmark, and Germany—is catalyzed by Hill’s inventive, hallucinogenic works on paper completed within the confines of his parental home once released from St. Lars mental hospital in Lund. Like memento mori, the allure of Hill’s works echoes in the symbolist ethos of Svanesang. An artist of the Romantic period, though displaced from the cannon of the movement due to the condition of his illness, Hill’s conjuring of landscapes—erratic and tender visions in charcoal and pastel—imagine an inner spirit, or ghost, of nature. Amid the forests and fields of countryside he would have once seen during his early career in France, his late drawings often feature places, such as deserts, waterfalls, and escarpments, where he had never been. His hand describes the behavior of the natural world in ways that no one else could. In response to the industrial era, a criterion of the Romantic masterpiece hinged upon the ability to engage with the philosophical position of man vs. nature. In the work of Hill, substantiations of a ravaged mind, nature wins.

[12] Andersson and Tal R, CHART, August 29, 2021.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

“Skeletons are a very banal thing, we all have them inside of us.”

Tal R, At tegne skelet [She draws the skeleton] (2016). Pigment and rabbit skin glue on canvas, 128 x 94 cm.

Courtesy of the artist, Galleri Magnus Karlsson & Galleri Bo Bjerggaard

Mamma Andersson, Jag [I], 2016. Oil and acrylic on panel, 149,5 x 122 cm.

Courtesy of the artist, Galleri Magnus Karlsson & Galleri Bo Bjerggaard

The consequences of a myth, such as Leda and the Swan, so embodied in art imposes a blueprint on the present. The retellings of its narrative returns in cycles, like seasons of undetermined length, reach out from the past to meet us when relevance takes seed. Perhaps, like the apparition of birds when winter thaws, they are not the same—still, we identify with the versions we know. For Yeats, the reverberations of a single act had the power to undulate and transform history. In his correlation, without the rape of Leda, Helen would not have been born and Troy would not have fallen, “A shudder in the loins engenders there / The broken wall, the burning roof and tower / And Agamemnon dead. [15] In a period of reckoning with history’s violent scars, when nature in the form of a global pandemic brings us to our knees, we question the origins of what we know. Of how we can connect to one another, of how we can be good lovers.

We wonder what would have happened to Leda without the swan, and how this text would have turned out differently.

This text results from a talk that took place during CHART 2021 in advance of the artists’ forthcoming collaborative exhibition at the Malmö Art Museum (Sweden) and Kunsten Museum of Modern Art Ålborg (Denmark) with C.F. Hill.

[15] Yeats, “Leda and the Swan.”

Mamma Andersson & Tal R: Svanesang. Installation view, Galleri Magnus Karlsson, Aug - Oct 2016.

Courtesy of the artist, Galleri Magnus Karlsson & Galleri Bo Bjerggaard

Stephanie Cristello is a contemporary art critic, curator, and author based in Chicago, IL. Her work focuses on artists who critically engage with the image and its role in visual culture. Through the lens of Classics and mythology, her diachronic writing practice concentrates on the intersection of ancient narratives and conceptual practice post-1960. Her research is specifically motivated by contemporary works that interrogate how language, text, and the use of poetic devices influence and shape the cultural and historical structures that surround us. She has worked internationally across a variety of platforms, including exhibitions, panels and symposia, editorial and publishing, and has contributed to numerous exhibition catalogues nationally and internationally.

Tal R (b. 1967 in Tel Aviv) lives and works in Copenhagen and has become one of the leading international contemporary artists. With coarse brush strokes from a relatively modest color palette, Tal R has a characteristic expressive way of painting. His work is represented multiple public collections, including Louisiana Museum of Modern Art (DK); Museum Kunstpalast (DE), Moderna Museet, Stockholm (SE) and Kiasma (FI). Tal R is represented by Galleri Bo Bjerggaard.

Mamma Andersson (b. 1962, SE) lives and works in Stockholm and is one of the Nordics most well-established contemporary artists. Inspired by filmic imagery, theatre sets, and domestic interiors, Mamma Andersson‘s compositions are often dreamlike and expressive. Her work is represented in multiple museum collections, including MOCA - The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (US), MoMA - Museum of Modern Art (US), Baltimore Museum of Art (US), and Moderna Museet (SE). Mamma Andersson is represented by Galleri Magnus Karlsson.