The first time I saw a painting by Magnus Andersen (b. 1987, Elsinore; Denmark) it reminded me of a rumour from my childhood about what would happen if you ate too many carrots or drank too much Sunny D. Both are rich in beta-carotene — the reddish pigment that gives the vegetable its signature colour — and apparently would cause children to develop distinctively "orange" appearances if they consumed either in an excessive amount.

Many of the figures in Andersen’s paintings share a saturated version of this complexion, but it is also the exaggerated and humorous undercurrent that flows through much of his work that reminds me of these stories and that makes the artist’s imagery so appealing to me.

His practice suggests an engagement with and mimicry of certain popular ideas relating to the question of 'how we should live'. The specific attitudes that Andersen seems most interested in are the same ones that encourage sustainable consumer behaviours but also that place particular emphasis on an obligation towards intellectual expansion and the maximisation of wellness through abundant rest and relaxation.

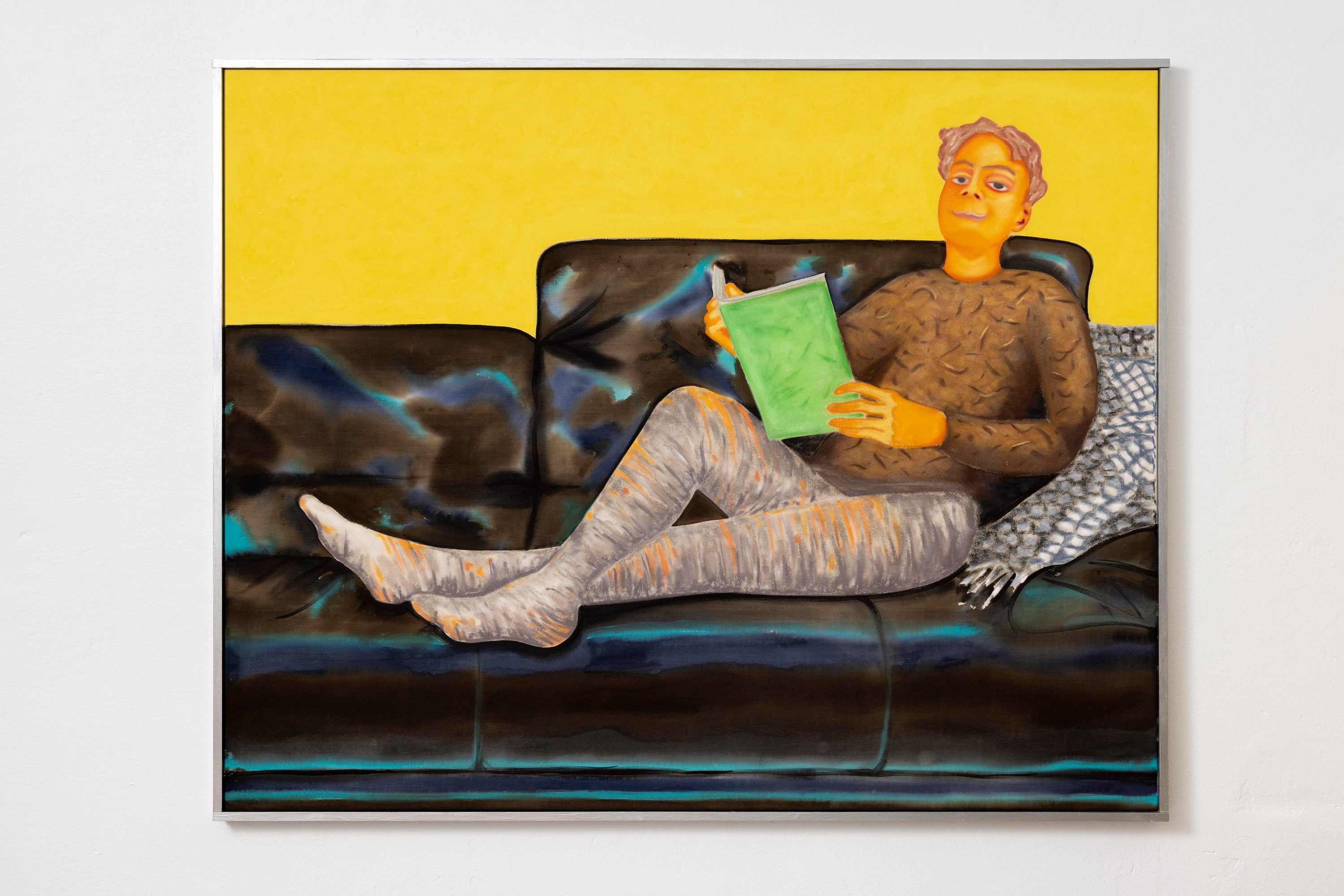

Magnus Andersen, Reader (Leather), 2022

Courtesy of the artist and palace enterprise. Photo by Jan Søndergaard

Magnus Andersen, Mogens and Other Stories, installation view

Courtesy of the artist and palace enterprise

Andersen’s paintings do not seem anti-intellectual and I think that they genuinely do advocate for environmental responsibility from behind a veil of semi-ironic nostalgia. At the same time I think they also challenge a certain preoccupation with personal comfort and parody the same kind of economic privilege that re-positions words like ‘ecological’ and ‘natural’ as brand indicators for an affluent middle-class lifestyle.

Andersen’s work is heavily indebted to several art historical developments from around the late 18th and early 19th centuries. One of these is the Biedermeier aesthetic and its specific interest in depicting scenes of aspirational daily activity. The intended audience for these works were the newly created urban middle classes who had become wealthy thanks to industrialisation and had subsequently emerged as newly viable patrons for the Arts.

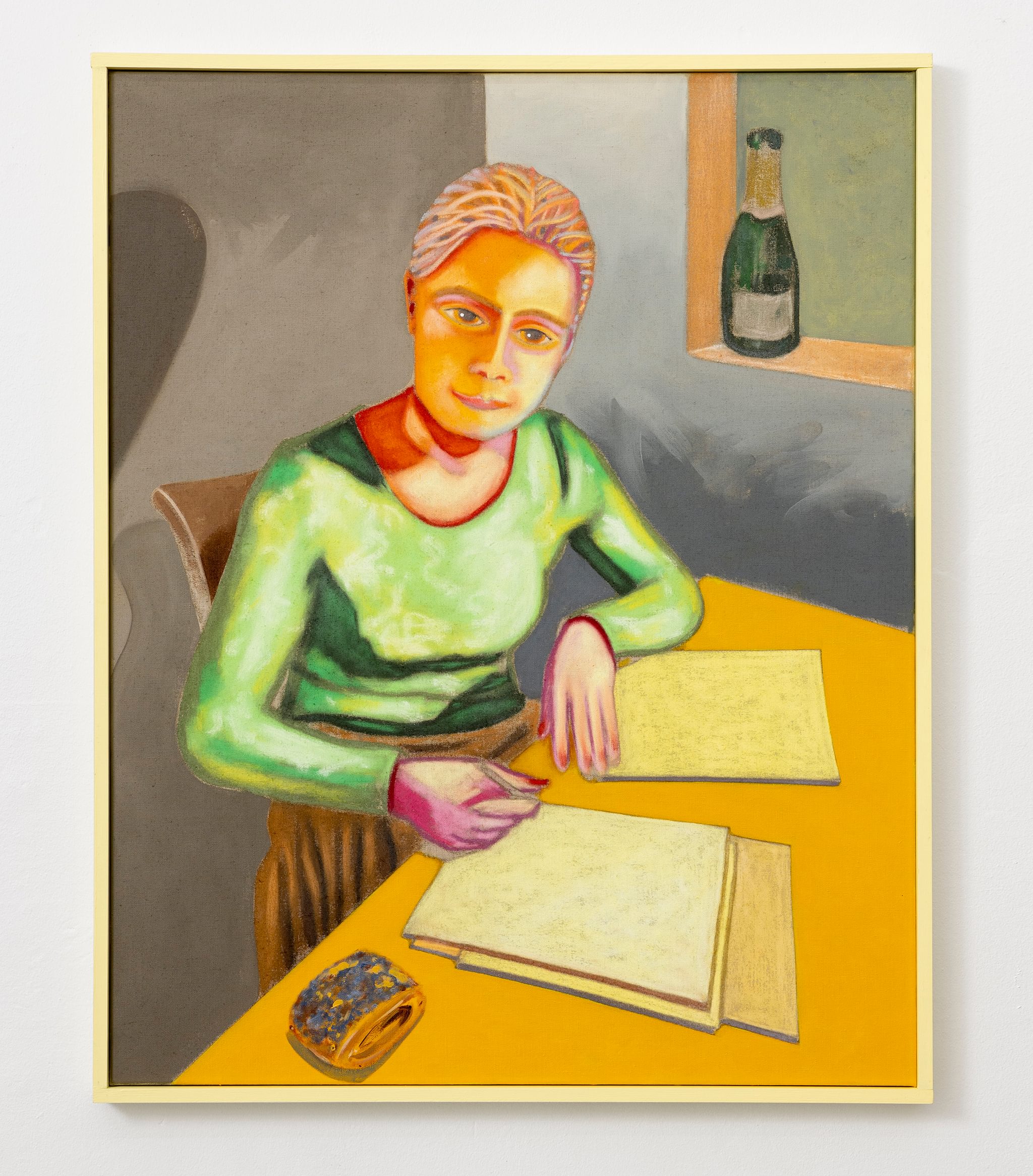

The figures depicted in Andersen’s paintings often appear ‘at-leisure,’ captured in the midst of quintessential domesticity. We find them reclining on a sofa, book in hand, or seated at a table lost in idle contemplation. Always there is a plated snack nearby should they get peckish, and Andersen’s focus on Nordic classics such as a BMOs (bolle med ost [“bun with cheese”]), Skagen toast and simple open sandwiches helps to locate his paintings inside the downplayed but materially secure cultural milieu of Scandinavian social democracy.

Something about the cartoonish exaggeration of these figures seems to indicate an omnipresent sense of banality and complacency, that asks: “is this really what we should be aiming for? Is this how our cumulative wealth is best spent?” At the same time there is a certain sense of intimacy fostered by these images that makes me think they might be an honest reflection of how a specific and relatively modest social group might fantasise about itself in a state of economic prosperity.

Magnus Andersen, Writer's Window (Tebirkes), 2022

Courtesy of the artist and palace enterprise

Magnus Andersen, Agrication, installation view

Courtesy of the artist and Tranen. Photo by David Stjernholm

Andersen’s work is also greatly influenced by a Romantic tradition of painting and indeed he readily borrows Romanticism’s anti-industrial, anti-capitalist and norm-critical focus on scenes from the natural world.

That being said, Andersen’s paintings cultivate a distinctly different impression to Casper David Friedrich’s panoramic landscapes and their subtle promotion of spiritual contemplation, away from the materialistic conventions of 18th century urban society.

Instead Andersen’s paintings present a cropped, exaggerated and vaguely sickly view of the rural landscape, encouraging a reversal of focus. To me, Andersen’s paintings suggest a turn away from the egocentric potential that an over-concern for one’s individual spiritual well-being might breed, particularly in the face of rampant industrial pollution.

Rather, these paintings encourage a certain uncanny self-awareness of our decisions as citizens and consumers by highlighting the potential link between the strangely stimulating yet desiccated landscapes in his paintings, and the increasingly hostile weather conditions we observe around us as the global climate crisis continues to intensify.

Whilst Andersen is obviously keen to avoid dogma and cultivate a productive sense of ambiguity in his paintings, his images do also seem to demonstrate a genuine social interest in the ways that forces of economic production shape our quality of life and our long-term relationship with nature.

Indeed the artist has previously referred to his paintings as ‘pedagogical images,’ but if the yellow characters in these images educate us as viewers, I think they do so in the same way as the Simpsons did - by framing social critique as satire, in a way that makes it more attractive, relatable and easier to consume.

Magnus Andersen, Agrication, installation view

Courtesy of the artist and Tranen. Photo by David Stjernholm

Magnus Andersen, Agrication, installation view

Courtesy of the artist and Tranen. Photo by David Stjernholm

Magnus Andersen’s point of departure stem from an interest in the relationship between image and representation, and how the living image and the painting function in a world heavily fueled with visual impressions. Andersen works with one of the most fundamental functions of the image; its pedagogical potential and through this, with themes such as education and training and how the medium of the image, historically, has been used to communicate this - from old-fashioned classrooms, feudal propaganda to contemporary advertising.

Recent exhibitions include: Mogens and Other Stories, palace enterprise, 2022, Readers Remedy, Damien and the Love Guru, Brussels, 2022, Agrication, Tranen, Gentofte, Denmark, 2021, Page at Petzel, Petzel Gallery, New York, US, 2021. Andersen’s work can be found in the collection of: Museum Sønderjylland, Tønder, DK, SMK National Gallery of Denmark, Copenhagen, DK, Collection European Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main, DE among others.

Oscar Gilbert is a gallerist and writer based in Copenhagen, Denmark. In 2019 he founded the contemporary art gallery OTP Copenhagen.