Animals—living, ornamental, and symbolic—are a recurring motif in Nina Beier’s work. The artist’s sculptures intervene in the circulation and consumption of mass-produced goods. She confronts mutable tropes found in a range of objects travelling between different geopolitical realities—many defined by their containing animal products. Beier’s plucking of goods from their virtual, imagistic existence is always timely. They become interesting to her precisely when their wild newness has peaked and they suddenly seem banal, cliché. This taming force defines human-animal relations in the West. Live animals, aside from their potential as food or raw material, are perpetually domesticated “as human companions”. John Berger, in the essay titled ‘Why Look At Animals?’, sees animals reduced to units of production and consumption in the global system of capital: “The category animal has lost its central importance. Mostly they have been co-opted into the family and into the spectacle.”

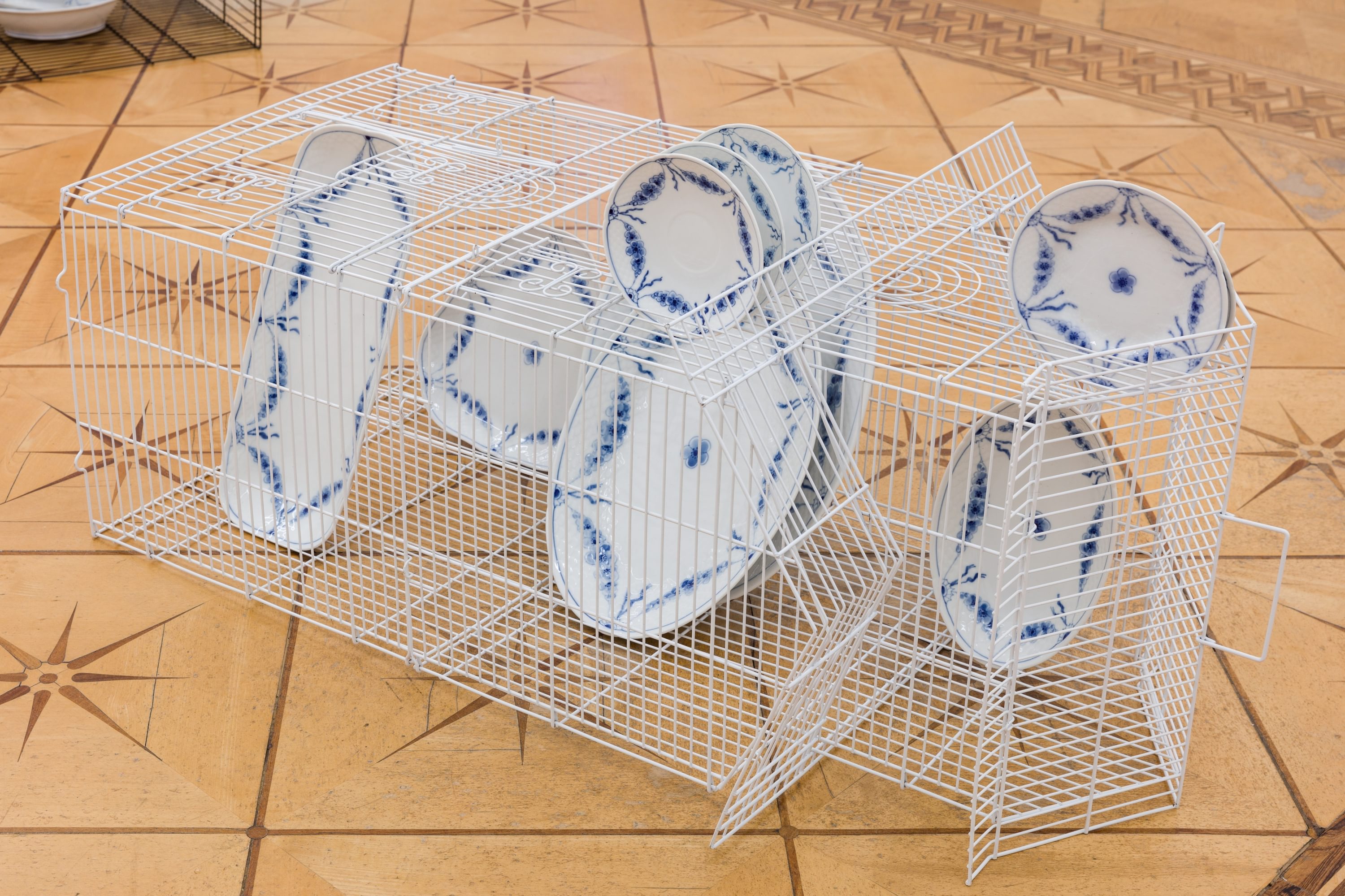

Nina Beier, Empire, 2019, Empire‘ Porcelain dinnerware by B&G/Royal Copenhagen and metal wire bird cage, 94 × 44 × 33 cm. Photo by Kunst-dokumentation.com.

Courtesy the artist and Croy Nielsen

In Beier’s performance Tragedy (2011), a dog is instructed to ‘play dead’ on a Persian rug in a gallery. The artist describes the scene: “The dog lies in an immobile pose, as if under a spell, unknowingly performing its own end.” The highly trained, professional dogs recruited to bravely play dead in Tragedy are rewarded for suppressing their innate try-hard eagerness, only to sustain indifference. In the abstract—as animal capital—we observe these dogs as representative of the practice of selective breeding for attributes such as alertness and hair that won’t moult, of which they are exemplary. Feminist theorist Donna Haraway offers an exuberant analysis of this phenomena in her essay ‘Value-Added Dogs and Lively Capital’ (from which this essay borrows its title). She explains: “In the flesh and in the sign, dogs are commodities, and commodities of a type central to the history of capitalism.”

Carved in stone and found at the boundary of a property, guardian lions are a symbol of authority whose elevated stature are intended to enthrall any visitor. In Guardians (2018), statuesque marble lions are placed incongruously through the galleries and other spaces of the museum. Beier explains: “Something happens when guardian lions leave their designated place at the entrance to buildings. They seem lost or maybe free, or both. Detached from architecture and ornament, they are no longer domesticated and become depictions of wild animals.” Beier filled the negative spaces of carved marble around each lion’s mouth, mane and muscles with congealed soap and beard trimmings. These accoutrements of cosmetic grooming—an activity that is considered to distinguish humans from animals—making the proud, liberated beasts slightly uncouth.

"In Empire (2019), shown at Chart by Croy Nielsen, a community of birdcages, adorned with archetypal Western sloped roofs or simplistic oriental flourishes invoke the image of a captured, caged animal. But instead of budgies, these domestic structures house pieces of hand-painted Royal Danish dinnerware."

Nina Beier, European Interiors II, 2019, installation view, Croy Nielsen, Vienna. Photo by Kunst-dokumentation.com

Courtesy the artist and Croy Nielsen

Nina Beier Empire, 2019, Empire‘ Porcelain dinnerware by B&G/Royal Copenhagen and metal wire bird cage, 49 × 98,5 × 45 cm. Photo by Kunst-dokumentation.com.

Courtesy the artist and Croy Nielsen

Gender tropes in contemporary domestic space naturally attract Beier’s scrutiny. In Beier’s series of exhibitions with the title European Interiors (2018–), pastel-coloured ceramic bathroom sinks—carrying connotations of feminine space—are arranged on the floor, unsupported, their drainage holes suggestively stuffed with fat cigars. It was the advent of capitalism that instituted the domestication of women. The notion of home, and its maintenance, seem to be a result of the devaluation of women’s labour into domestic work, reproduction, and caregiving—the design of interior spaces, furniture and appliances, compounding it. For animals, the interior, too, is a site of marginalisation, isolation, and dependence.

In Empire (2019), shown at Chart by Croy Nielsen, a community of birdcages, adorned with archetypal Western sloped roofs or simplistic oriental flourishes invoke the image of a captured, caged animal. But instead of budgies, these domestic structures house pieces of hand-painted Royal Danish dinnerware. Beier explains that “The birdcages replicate human architecture but in the sculpture they also double as dishwashing racks, both trapping and confining the china. Porcelain imported from China became collector’s items in Europe starting in the fourteenth century. Poor copies quickly followed, but it was only when the trade secret was finally cracked after 400 years that royal factories all over Europe started their production of knock-offs.” In Empire, tropes of domestication and domesticity are literally meshed. And as with all of Nina Beier’s work, she attempts to unravel the knot of soft power relations that coexist in the objects she chooses, exposing the transitory—and often latently violent—nature of society’s value formation in order to lay bare inbuilt social and economic structures—be it on a species, gender or global level.

.

Nina Beier (b. 1975, DK) lives and works in Berlin.

Nina Beier’s multimedia installations, performative sculptures, and static assemblages incorporate everyday objects into theatrical still lifes that examine the cultural symbolism embedded in them.

She has been exhibited widely at institutions including Kunsthal Gent (BE), Kunstmuseum St. Gallen (CH), Kunsthaus Zürich (CH), ARoS (DK), Walker Art Center (US), Kunstwerke (DE), Metro Pictures (US), Swiss Institute (US), and Kunstverein Hamburg (DE). She has participated in Riga International Biennial of Contemporary Art (LV), Performa 15 (US), and the 13th Biennale de Lyon (FR).

Vanessa Boni is an independent curator and art historian. With Kyla McDonald, she initiated a project dedicated to feminist exhibition-making and artist research (launching 2020). As curator at Spike Island, Bristol she curated solo exhibitions with Nina Beier and Mai-Thu Perret and led the 2018 Freelands Award with Veronica Ryan. Prior to this, Boni held curatorial positions at Eastside Projects and Liverpool Biennial.

Photo by James Langdon