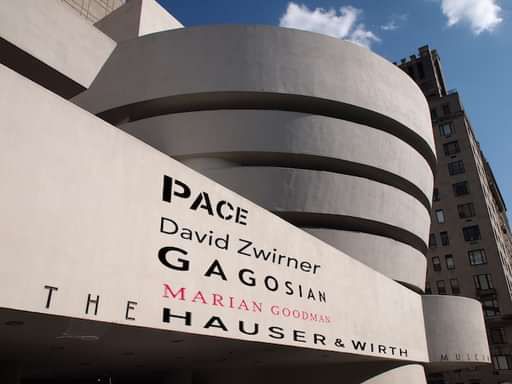

The "Pace; David Zwirner; Gagosian; Marian Goodman; Hauser&Wirth" Museum, first published via HyperAllergic in 2014

Image courtesy of Benjamin Sutton

"That son-of-a-bitch, give him two beer cans and he could sell them." — Willem de Kooning on Leo Castelli.

Seven years and nearly a third of a pandemic ago, a prominent web art magazine published a strangely adulterated image of the cylindrical exterior of the Frank Lloyd-Wright Guggenheim building. On its façade, where the museum’s shingle normally hangs, were Photoshopped the names of the planet’s five biggest art galleries—Pace, David Zwirner, Gagosian, Marian Goodman and Hauser & Wirth. The point of the digital defacement: to illustrate one survey’s findings that artists from those galleries dominate 75% of museum exhibitions in New York and up to 30% of institutional shows in the U.S..

Commissioned by The Art Newspaper, the 2015 survey raised a number of troubling questions. Among them: how was it possible that no one previously noticed Manhattan’s Guggenheim devoting more than 90%, of its solo exhibitions (eleven out of twelve between 2007 and 2013) to artists from the same five galleries? What did “the growing influence of a small number of [art outfits] in a rapidly consolidating art market” mean for the future of art? And, what does the public truly miss when a handful of corporatizing concerns effectively buttonhole museum fare?

Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Photo by Reno Laithienne

Here’s an even more basic head-scratcher: how did the world’s most successful art dealers—the art world’s equivalent of the planet’s biggest retailers: WalMart, Amazon, Costco, Home Depot and Kroger—become supreme tastemakers in a field whose basic coin, art, is purportedly judged by criteria (quality, originality, criticality, historical influence) other than commercial success? There is, as one might expect, a history to these developments that merits examination…

In the 1950s—when art critic Clement Greenberg browbeat dealers into showing Abstract Expressionist painters and strong-armed collectors into buying their canvases—the art world hierarchy did not necessarily favor the dealer. Ditto for the period in which artists were their own gallerists (“a ghastly [1980s] neologism” per critic Robert Hughes, the term is now perfectly interchangeable with the older “dealer”).

According to lawyer and art scholar Mark A. Reutter, “even Rembrandt and Vermeer acted as dealers” in seventeenth century Holland. “Clients could also commission works,” he writes, “but the rule was that the dealer displayed a selection of paintings that were for sale”—a practice that even extended to works that were not produced by the artist’s hand or his atelier.

In turn-of-eighteenth-century France, the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture fundamentally revolutionized the artist’s social position but also significantly upended the trade. If members were guaranteed “the right of free exercise of the arts,” they were prohibited from running their own shop or “from displaying their paintings in the windows of their studios.” In 1737, sales and representation became largely associated with the official Salons; in time, these shows came to stifle both refusé artists and their budding dealers. Enter the 19th century “marchand-amateur,” which Reutter also refers to as “the systeme marchand-critique.” Then as now, it turns out, it was independent dealers that translated difficult, often iconoclastic new forms into comprehensible concepts for the art-loving public.

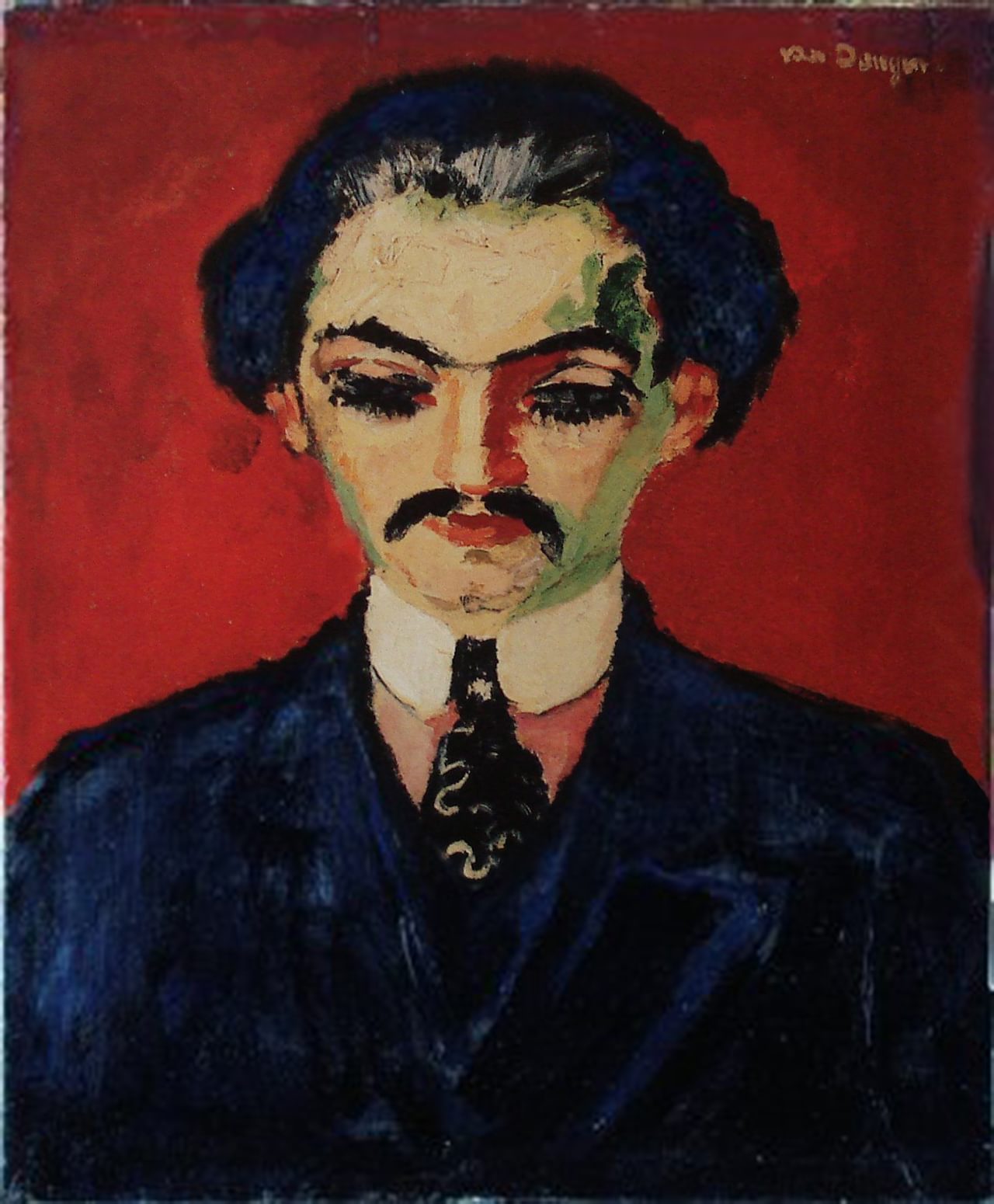

Kees van Dongen, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1907-8, oil on canvas

Courtesy of the Musée du Petit Palais, Geneva

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Portrait of Paul Durand-Ruel, 1910, oil on canvas

Photo: The Yorck Project (2002) 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei (DVD-ROM), distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH. ISBN: 3936122202.

The rise of Paris as the world’s leading art city produced legions of marchands over several generations. Few were cleverer than Paul Durand-Ruel (1831-1922). Considered the first modern art dealer, Durand-Ruel expanded his role from middleman to all-important promoter-manager-and-artist-banker. The first dealer to support his stable with monthly stipends, he transformed the family stationery shop into a dedicated gallery which he later expanded with subsidiaries in London and New York. Among his purely aesthetic discoveries: the realists of the Barbizon School and the Impressionists, the last of whom he took from penurious obscurity to the moneyed sparkle of the era’s electrified salons.

What Durand-Ruel achieved for the Impressionists, Ambroise Vollard (1865-1939) did for the Post-Impressionists and Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler (1884-1979) for the Cubists. While Vollard earned the respect of artists like Paul Cezanne, Edgar Degas, and Pierre-Auguste Renoir for buying up large chunks of inventory to resell at huge markups, Kahnweiler pioneered the idea of the exclusive relationship between artist and dealer. Only restrictive representation, he argued, justified major financial risk. Among the first dealers to embrace the long view of working with living artists, Kahnweiler’s market stewardship and connoisseur’s eye recommended him to giants like Georges Braque, Fernand Léger, and Pablo Picasso.

"Considered the first modern art dealer, Durand-Ruel expanded his role from middleman to all-important promoter-manager-and-artist-banker."

Alfred Stieglitz, ‘The Picasso-Braque Exhibition, “291”, 1915. Platinum print, 19,5 by 24,7 cm.

Courtesy of the artist and the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art

In New York, the gallery land-grab that began with European transplants like Knoedler & Company in 1846 and Wildenstein & Company in 1903 was followed by rockier American experiments like photographer Alfred Stieglitz’s Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, opened in 1905, and Julien Levy’s eponymous outlet, launched in 1931. Neither had much money or business acumen. Steiglitz (1864-1946), for one, was loath to sell art: he once asked a collector what made him think he deserved to own a watercolor. Levy (1906-1981) bravely battled American philistinism but was laid low by the Great Depression. According to Ed Winkleman and Patton Hindle, authors of the 2018 edition of How To Start and Run a Commercial Art Gallery (Skyhorse Publishing), both gallerists were early twentieth century personifications of a frustrated twenty-first century phenomenon—dealers who remain influential despite not being "very successful businessperson[s]."

If critics like Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg briefly held great sway over the American art scene in the 1940s and ‘50s, by the time the 1960s and ’70s rolled around they had returned, like swallows to Capistrano, to the less influential role of commentators. Among the crop of new post-World War II dealers were Betty Parsons (1900-1982), Sidney Janis (1896-1989), and Leo Castelli. The latter’s surname, besides identifying the Trieste-to-New-York transplant who kicked off Pop Art and closed the door on Abstract Expressionism—hence Willem de Kooning’s complaint about Castelli’s spectacular salesmanship—became shorthand for an ever-expanding period of seemingly recession-proof sales that, at the top end, extends into our present era.

Portrait of Betty Parsons, 1977

Photo by Lynn Gilbert, this file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

The Castelli Model, as it has come to be known, was initially established in the go-go 1960s—after Andy Warhol silkscreened his first Campbell’s Soup Cans and Robert Rauschenberg’s nabbed the Golden Lion in Venice—and was then passed down like a gold baton to the dealer’s business juniors. These included gallerists Michael Werner, Mary Boone, and Tony Shafrazi, but most notably Larry Gagosian and Jeffrey Deitch. To his star students Castelli bequeathed not just prominent collectors like Condé Nast publisher Si Newhouse (Gagosian) and his entire mailing list (Deitch), but the very idea of the mega-gallery—not just multiple showrooms deployed around art capitals like properties on a Monopoly board, but a globe-girding plan for world art domination predicated on strategic arrangements with international galleries, museums, curators, and collectors. That very same chummy, speculative, deep-pocketed arrangement, with important app-like updates, effectively covers the planet today.

Jasper Johns, Painted Bronze (1960). Inspired by Willem de Kooning's remark about Leo Castelli: "That son-of-a-bitch, give him two beer cans and he could sell them".

Courtesy of the artist and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

The Castelli Model not only prefigured a multi-decade global dealer expansion, it set the template for the continued existence of today’s mega-galleries. According to Winkleman, “Leo Castelli did not invent many of the strategies behind his unparalleled success at selling contemporary art”—relentless promotion, generous stipends, an understanding of the gallery and its artists as brands, the courting of museum directors and curators, public relations offensives that are no less effective for appearing financially bottomless and effortless—"but he optimized a series of ‘best practices’ for art dealing in a way that was so admired by artists and younger dealers alike that it unofficially became ‘the way it’s done.’” A key caveat remains unspoken: so long as gallerists could afford it.

This is how the road to the Guggenheim via Art Basel Miami Beach was cut and paved. As tens of thousands of smaller shops reassess the oligopoly established by the art world’s five megastores—and the globe emerges into the period economists have equivocally dubbed “The Great Reset”—it’s up to another cohort of galleries to chart a more equitable and sustainable way forward. Less monopolistic, more representative art territories beckon.

Louise Bourgeois, Spider, 1996, Installed at Hauser & Wirth Monaco

Photo by Liza Uleksina

"[...] it’s up to another cohort of galleries to chart a more equitable and sustainable way forward. Less monopolistic, more representative art territories beckon."

Christian Viveros-Fauné has worked as a gallerist, art fair director, art critic and curator since 1994. He currently serves as curator-at-large at the University of South Florida Contemporary Art Museum. Photo by Will Lytch.