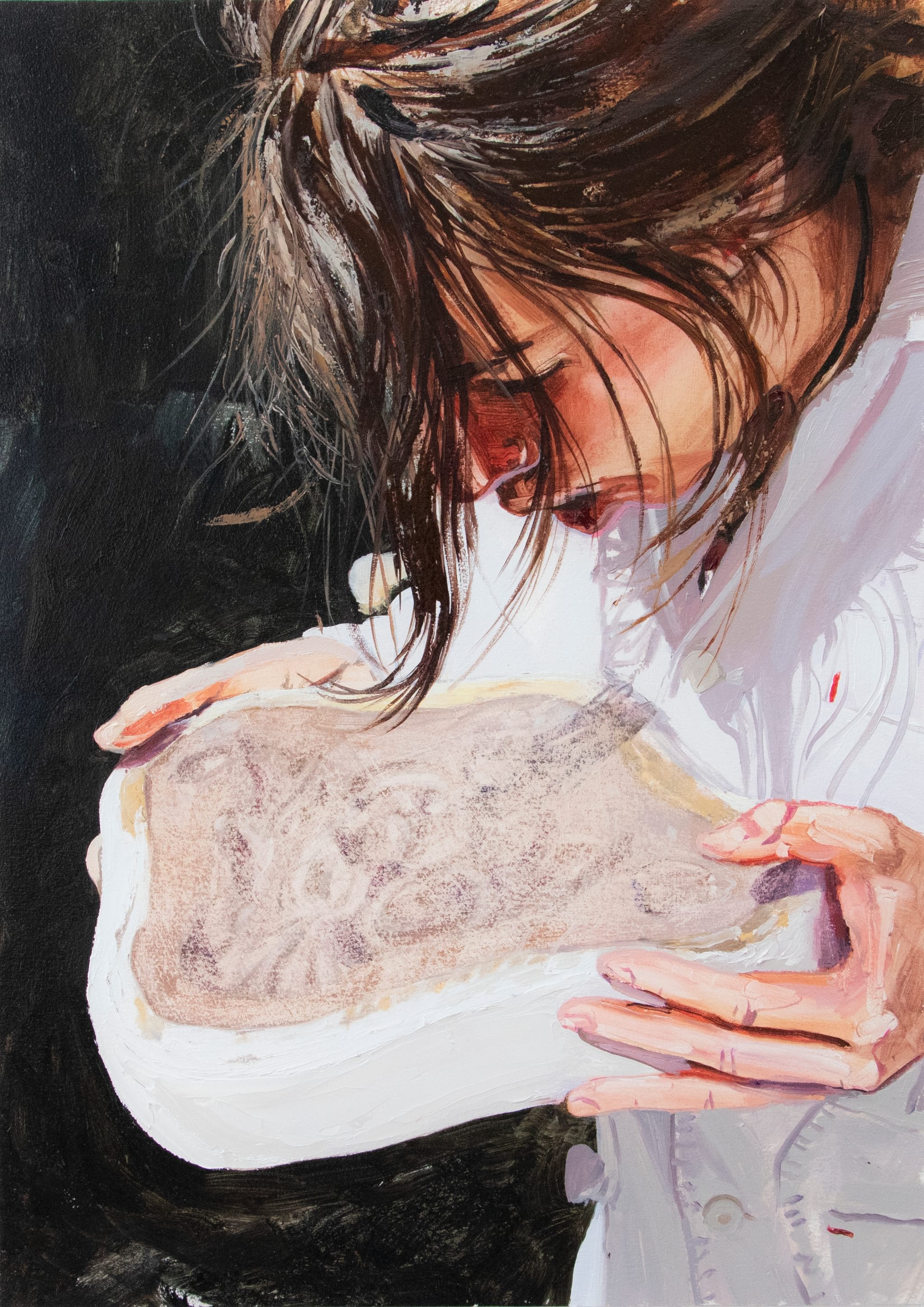

Sara-Vide Ericson, Consequence (Exhaust), 2020, oil on panel, 50 x 70 cm,.

Courtesy the artist and V1 Gallery

A woman in a chair appears to find new form under the weight of the brushstrokes that define her presence in a room of intense proportions; another exists on the canvas as a result of a few paint-loaded streaks, accurate enough to convey so much more about her than the action she is engaged in; a third, her head physically squashed between the layers of soft furnishings, who might be described as having found some temporary ‘space’ outside of the worldly pressures she is subjected to, or need to convey as the lead actor in an image.

When I look at paintings of people, I want to see how they have revealed (been encouraged to reveal) something of themselves during the process, and negotiated the act of being a living object under scrutiny. Or alternatively, how it feels to be thrown into the moment of capture without warning, where individuals or groups of people are presented remotely, lost in a range of states, whether in thought or in action; how we can never see ourselves but frequently experience being the remote observers of others. Then again, if the source material of the painted subject is second-hand, explore how we can discover something about the artist rifling through the layers, connecting the modes of reproduction in play—between the image as existing artefact and its re-delivery on canvas. And finally, how they have sought their own way of engaging with the history of the human subject as recorded through time-based media.

“I live all my paintings before I make them.”

Chantal Joffe, Esme Looking Down, 2018, original lithograph, printed on 300g Velin d’Arches paper, 50 x 35 cm. 20 ex. numbered and signed by the artist. Photo by Lars Gundersen.

Courtesy the artist and Edition Copenhagen

The group of three female artists under inspection here is remarkable for the ways its members deal with these issues in the day-to-day practice of painting. Moving amongst images of their works, one is afforded multiple viewpoints of the human subject, as a historical trope and as the focus of real-life encounters. Over and again, we are seduced, called into the associative margins between very different approaches to representation: whether considering the variants of each practice or their output as a collective. In the gallery round, or via the digital swipe, we might in a single experience negotiate the variable entanglements of the sole sitter in the line of the artist’s gaze; the figure as the bit-part representative in a scene; or having been abstracted into a living-motif designed to embody a wealth of potential external concerns.

Chantal Joffe paints from life and other sources. The protagonists of her canvases are depicted in all manner of human states and referential nets. The bold central positioning of each subject, and their often slightly askance circumspection of us as viewers, is essential to our engagement with them. They occupy each canvas, either as willingly vulnerable subjects caught in the pinch of being seen, or as perfectly imperfect characters released from the time-based narratives in which they were originally frozen. Through Joffe’s framing, they all become individuals with a curious story to tell, depicted with deft fluidity in paint as a set of human ‘tells’, possibly unwittingly revealed for public observation.

A contemporary disciple of the great Alice Neel, Joffe invites us into the most direct of human encounters—the portrait—with characteristically louche, but ultimately controlled abandon. Big, fat brushstrokes of carefully choreographed tones describing the planes of faces, the folds of apparel, and limited site-specific clues, appear to approximate a sense of the subject being observed from a casual personal distance, yet have clearly been developed into an intimate short-hand that will provide points of entry into what is always a psychologically complex image. Given the seated or prone formality of the poses, some could be subjects in therapy, and our response to their presence—whether one of connection or distance—inevitably reveals much about us as viewers.

Sara-Vide Ericson, Consequence (Reef Knot), 2020, oil on canvas, 35 x 44 cm.

Courtesy the artist and V1 Gallery

Sara-Vide Ericson, studio view, 2020.

Courtesy the artist and V1 Gallery

Sara-Vide Ericson channels everyday profundity with the intensity of a method actor or a musician in pursuit of a concise lyrical form. Her diaristic paintings describe the experiential strata of a figurative world that simultaneously support existential angst as the existence of accidental malapropisms. Sometimes they depict people in context, but often they appear to present crowded environments, where the figure is treated as just another facet of the scenography. Certain new works feature the artist herself. Clad in shirts and functional trews, draped or wrapped in fabrics, Ericson appears as an intrepid cowgirl-adventurer in the rural Swedish landscape, engaged in a range of essential—if oddly mystical—tasks and moments of reflection.

In a recent video interview, Ericson states: “I live all my paintings before I make them.” A key—if not necessarily literal—fact when considering what it is about her particular faithfulness to representation that eludes obvious categorisation. Her works may offer representational tactics that we recognise, but they also appear like visual records, histology slides, of the making process itself. The staging of each composition and the sculptural qualities of the details—living spaghetti-strands of hair, origami-like creases in leaves and sheets, weighty shadows that threaten to consume the subject—describe the shifts between her sources—direct experience and reproduction. As a result, we are able to move at will, around the performative actions at the heart of the work, the artist’s renegotiation of this experience as studio evidence and the physical act of translating it into paint.

Both persuasively staged and incidental situations inform Anna Bjerger’s investigation of the figure in context. Working from found imagery, she constructs seemingly simple narratives that play with the seductive nature and highly effective methods of the editorial campaign and the public presentation of personal information. In the journey from image to painting, Bjerger imbues her starkly cropped or wandering strangers with the power to connect us with possibilities missing from both: sensory territories, the economic imperative to garner consumers, or the amateur need to catalogue events. Images, like objects, she reminds us, are ripe for our collective projection and her painterly manipulation of it. As the custodian and moderator of second-hand visual strategies, Bjerger is able to re-acquaint us with the more mysterious aspects of our individual susceptibility to certain imagery.

"When I look at paintings of people, I want to see how they have revealed (been encouraged to reveal) something of themselves during the process, and negotiated the act of being a living object under scrutiny."

Anna Bjerger, Ocean, 2020, oil on aluminium, 128 x 90 cm. Photo by James Aldridge.

Courtesy of the artist and Galleri Magnus Karlsson.

With the gradated blear of an expertly brushed tonal layer, for example, or by zooming in on a pictorial component, Bjerger is able to create harbingers from a rolling cast and extract moments of potential magnitude from banal imagery. Liquid legs in tights, atomised swarms of insects over the heads of children in summer, and sinewy skiers in endless performative repeat materialise in or out of the design-savvy or nostalgic set-ups they belong to. Through her minimal treatment of ready-made images, Bjerger alerts us to the stylistics of image-making, the codified messages within them, and their influence on the encounter. But, most importantly, she uncovers the uncanny sense of time collapse that can occur through the processes of looking and relating; between ordinary life unremarkable as it was, and the change that can come with a shift of perspective.

All these approaches to the figure convey a sense of both physical and mental movement and the visceral nature and hidden minutiae of everyday gestures in a given scenario. This might be as a result of the intense process of first-hand studio observation and the subsequent distortion of the subject this intense activity can lead to. Or, through the re-articulation of an image, as it might be collectively perceived. And, of course, the culturally-specific idiosyncrasies a lived moment made-static can reveal: the material facets and colourways associated with modes of recording life, through time, which inform the shape of our memories.

Rebecca Geldard is a writer, editor and curator based in Powys, Wales. She has contributed regularly to a variety of press and art publications, while her essays and short fiction feature in many books and catalogues. She is Associate Director at Coleman Project Space in London, and has recently launched the online art platform appleandhat.com.