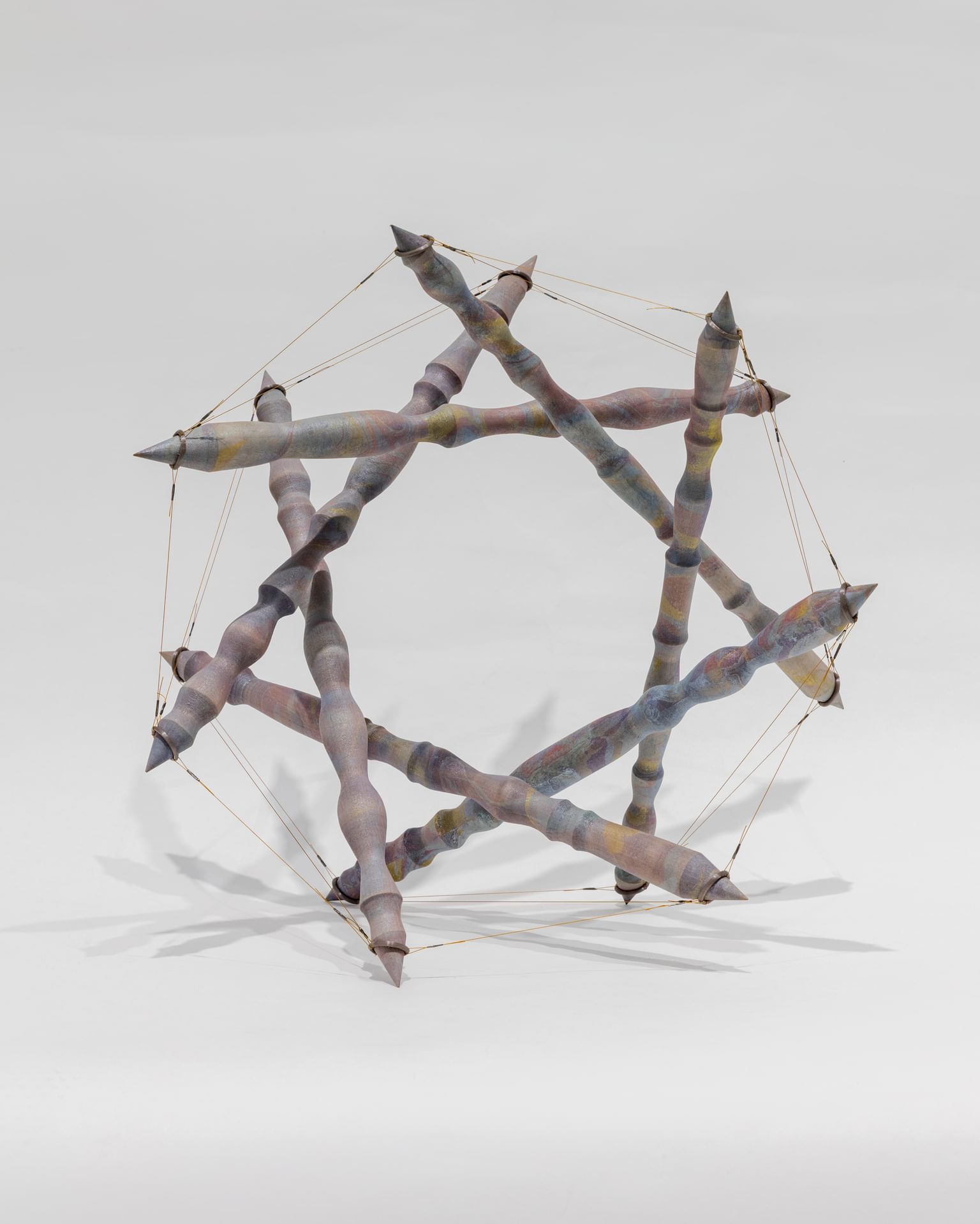

Bella Rune, Vertical Network Performance, installation view, 2018

Courtesy of the artist & Galleri Magnus Karlsson

I know that Bella Rune makes her work but I don't quite believe it. It feels found. I know the works exist here and now but I also have a niggling feeling they aren’t fully here, now, they’re partly somewhere else and maybe, sometimes, they’re completely somewhere else, in some other time, but I can’t locate where and when that would be. I’m fully aware that it’s new but I don’t completely trust that, it feels like it’s been around longer. I wouldn’t be surprised if I saw a fragment of one of her works appear in my Twitter feed, a 3D printed version of her head with its distinctive bowl haircut, 2 cm tall, dredged up out of deep storage at The Met. Or some strands of mohair thread, dyed with cyan printer ink and curry powder. Her work frustrates me, disturbs me and de-stabilises me. It’s also deceptively (but joyously) light, decorative and beautiful.

She told me she wants the works to feel like they’re in a room but seen out of the corner of your eye. They are present but not the focus. She also said she wants them to be the pebble in our habitual shoe. I asked her where do your works exist? She understood what I meant immediately. She answered, it's a triangulation - language - temporal - (and without mentioning it, obviously, the ‘sculpture’ itself but that somehow is the least important part). She said the work needs to be activated. This is literally true with the digital works, they need to switched on and buttons need to be pushed. It’s equally true of all the works though. They can be folded away metaphorically. Her 6m tall hanging mohair towers can also be … into a family sized pizza box.

Anonymous (moche), Portrait Vessel, AD 50-800, Red, orange and gray earthenware, 20,9x16,5x13,9 cm

Image courtesy of the Walters Art Museum.

Portrait vessel, Moche style, North Coast Peru 100–800 C.E. Ceramic H: 26.5 cm

Image courtesy of the Fowler Museum at UCLA. Photo by Don Cole.

I follow a lot of automated bot accounts on Twitter which trawl museum archives and post images of objects they find. These are often objects in deep storage which will rarely, if ever, see the light of day again. They will certainly never be displayed in the museum. They have been found, identified, acquired, photographed, digitized, placed in a storage box and deposited in a climate-controlled basement room, to die. The objects are often lowly, broken, worn down, incomplete or badly made: a clay head (it’s body lost), a section of architrave, a bit of finial, a hair clip, a piece of pierced bone. Here is a typical example of what one of the automated bots might drop onto my timeline: a black and white photograph of a small, crudely made human head with one ear missing. It is labeled: “The Met Museum. Ornament: male head, ca. 15th 14th century B.C, Geography, Mesopotamia or Syria, Medium, Glass, Dimensions, 2.13 x 1.75 x 0.99 cm, Gift of Sheldon and Barbara Breitbart, 1984, Accession Number, 1984.453.5.”

I think of these appearances as being like visitations from the ghosts of dead objects, buried in museum storages all over the world. They first existed in the imagination of the maker or the person who wished for it. Then they became language. Next they became material. For a while they existed as useful, usable, objects. They belonged to somebody, they were a possession. Maybe they changed hands, passed down through a family, or they were traded, bought and sold. Maybe they lived where they were made, maybe they traveled the world. Then they were physically lost in the dirt or lost their significance or ritualistic meaning. Years later they were re-discovered. Dug up by an archeologist, unearthed at a market, found in a drawer in the basement of a castle. Then they were absorbed into a museum collection and ended up in the box we know about. Now, they are living a final stage of life as a digital spectre, possessing our timelines.

Bella Rune, Cradle of Cognition, detail, 2021, Wood, pigment, string and bioplastic, 120x120x120 cm

Courtesy of the artist & Galleri Magnus Karlsson

Bella Rune, Spinning, 2021, turned birch wood, nail polish, wire and bioplastic, 50x57x24 cm

Courtesy of the artist & Galleri Magnus Karlsson

Bella Rune is interested in the ‘constant re-writing’ of the history of human artifacts: “The boundaries of ‘modern man’ are constantly being pushed by new discoveries. What is now said to be the oldest cultural or artistic object created by mankind? The discovery of Hilma Af Klimt’s paintings forced a re-write of the history of abstraction. Some 73,000 year old zig-zag scratchings found in a cave shift, again, the beginnings of man’s artistic adventure. I am still trying to connect people, architecture, history and different material histories through sculpture. I want to make sculptures that are both very materially realistic and also have an unreal quality, in-spite of being still in mid-action, or in a permanent state of tension. I try to merge different elements of knowledge and references and often return to thoughts about the history and systems of making and building through models. During COVID and with forestry on my mind, I have turned to wood, turning, joining and painting, but I have also include 3D scanning and printing in the work, something which lets me play on both sides of the screen.”

Rune’s works do exist in different realities, physical and digital. She has produced several works using Augmented Reality but she is against Virtual Reality because that locates her work too fixedly in one realm. It needs to have the ability to leak, as she says, between realms. She wants there to be mess, weight, slippage, errors, imperfections. After watching a recording of a talk she gave at The Garage in Moscow I mentioned to her that she speaks a little like a designer. She seems to approach projects like a designer would tackle a brief, responding to a problem that needs to be solved - a puzzle that needs to be solved. She laughed and slightly agreed but said she didn't want to make people's lives any easier. She says maybe she thinks like a designer but without rationality. One of the important differences between art and design is that art is always speculative. It is never resolved and never aims to be so. When Bella Rune finds a solution for the problem (which may have never existed anyway), that’s it. It doesn’t go into testing and production and scaling up. It’s always the prototype.

"I want to make sculptures that are both very materially realistic and also have an unreal quality, in-spite of being still in mid-action, or in a permanent state of tension."

Bella Rune & Galleri Magnus Karlsson, CHART 2021, Installation view

Courtesy of the artist & Galleri Magnus Karlsson

She talks about designers of repeat patterns. That they want their work to cover the world, metre by metre. To repeat and repeat, endlessly, suffocatingly. Digital networks have the same intentions: coverage. She is fascinated by the idea that pattern designers work with the awareness that their two-dimensional efforts are incomplete until another designer, outside of their control or complicity, turns them into a 3D object, a cushion, a bus seat, a pair of shorts. Everything they make is an unwitting collaboration. I think this is what she means by activation. She says that when she was young she knew artists for whom it would be taboo to consider the interests of the audience. The ideal state of the exhibition space for them was devoid of people. She says she finds the images of empty exhibition spaces fascistic. When she makes an exhibition she wants to know who’s space she is entering. Who works there, who does the cleaning, who visits. They activate the works. They transform them from 2d cloth into cushions, bus seats and pairs of shorts. I think what she’s interested in and wants to believe in, is the civilizing power of culture, of art and design. That maybe progress is possible beyond the failed project of modernism and without a final descent into totalitarianism and fascism. I have no idea how six-metre-tall weavings of Day-Glo mohair convey any of this to me but they do and that is what gives me faith that she might be right. I hope she is. I trust her.

David Risley is an artist. He ran David Risley Gallery, in London (2002-2010) and Copenhagen (2010-2018). He was founding Co-curator of Bloomberg Space, London (2002-2005), Co-founder of Zoo Art Fair, London (2004), and Co-founder and Co-owner of CHART. He continues to write, curate, and develop projects with artists. He is developing a sustainability project for public-facing institutions.