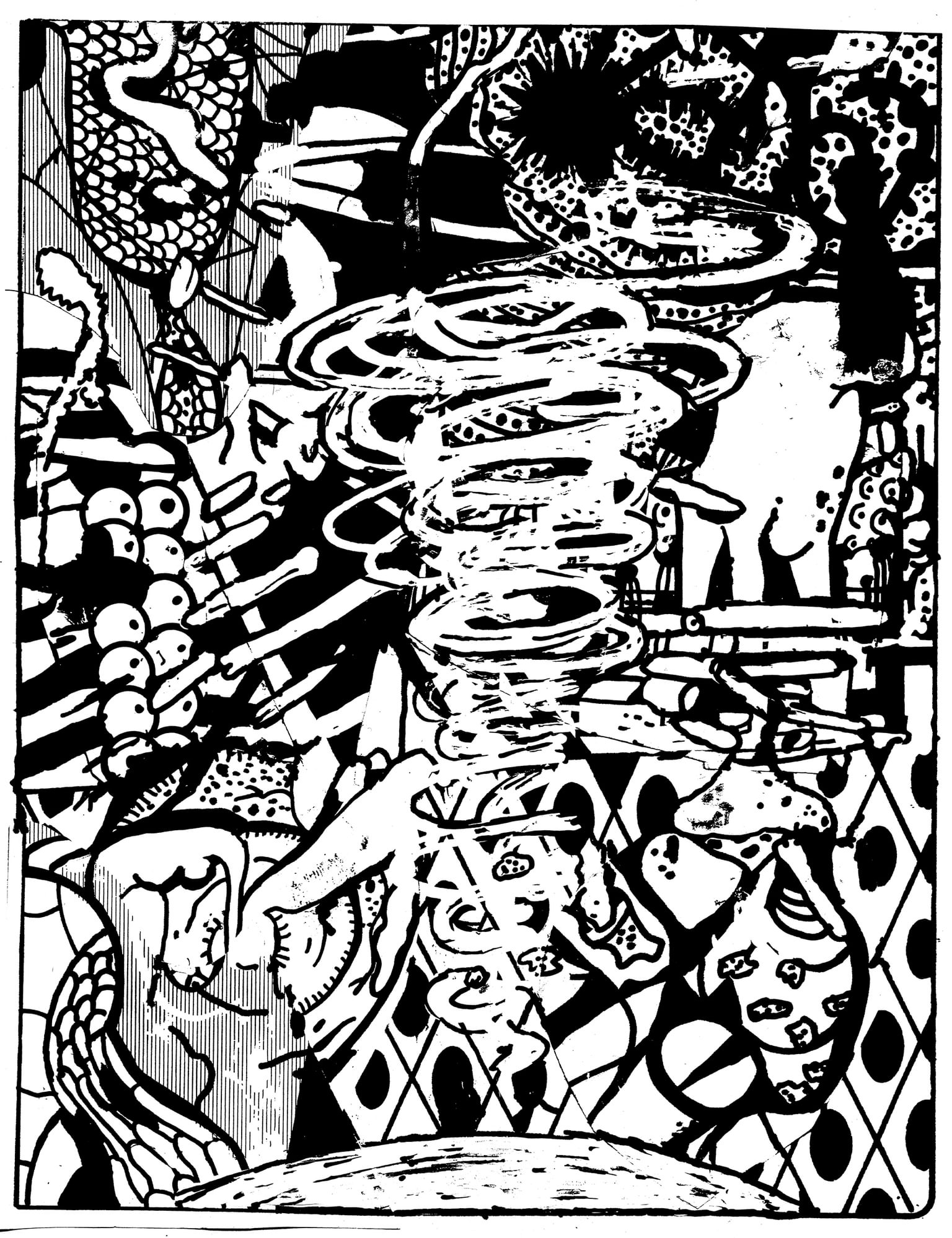

Neptune by Zven Balslev

Courtesy of the artist

The zine medium has, in the past, catered to everything from political activism, comics, punk fan journalism, hip-hop culture, the graffiti community and death metal enthusiasts - a broad spectrum of cultural interests that are usually seen as being too niche or radical to be covered by the mainstream media. A particular branch of zine-making referred to as the "graph’zine", a sub-genre of zine-making consisting entirely of graphic images, is being elevated to the status of an avant-garde movement in France.

We find ourselves in Paris in the late seventies; here, the punk movement is sweeping through France like so many other countries in this period. As a graphic accompaniment to the music, members of the artist group ‘Bazooka’ such as Electric Clito, Lulu Larsen (Larsen means guitar feedback in French, don't ask me why) and Loulou and Kiki Picasso, begin to edit various magazines and create cover art for the punk and industrial bands of the time. During 1977, several members of Bazooka were employed as illustrators at the newspaper Libération, and one night they succeeded in hacking the contents of the paper. Without permission, they wrecked the layout, moving columns and replacing photos with drawings, or adding texts and captions, often in complete contradiction to the content of the articles they were supposed to illustrate. The incident, viewed in retrospect as a kind of creation story for French graph’zine culture, divided the editorial staff and ended in mass dismissals. Many of the perpetrators later returned to Libération however, thanks to editor-in-chief Serge July. July called on the troublemakers to launch the project "Un Regard Moderne" (A Modern Look), a magazine consisting solely of drawings and illustrations that would be sold as a supplement to the newspaper. Five issues plus an Issue 0 were published in 1978, before the project was conclusively shelved and the contributing artists each went their separate ways.

Un Regard Moderne, Paris

Source: Gonzäi.com. Read more: librairieunregardmoderne.com

‘Un Regard Moderne’ would later also become the name of a bookshop in Paris that played an important role in the development of the graph’zine phenomenon. Bookseller Jacques Noël begun dedicating a small section of his shop to independent zine publishing in the late 1970s. Beginning with imports from Japan and the USA, Noël would later go on to stock home-made books and booklets produced by a wider community of Parisian locals. Pakito Bolino, founder of the publishing house Le Dernier Cri, was one such publisher that Noël partnered with at an early stage: "At first I went down to him [Noël] and complained. Nothing happens here, everything is so boring! Jacques replied: You can just do it yourself, publish books yourself... and he didn't just say it to me, so... It's his fault! And the bookshop really developed thanks to us making zines, that's what the underground scene is all about. Making things that deviate from the norm, and then giving them space to grow freely. In other words, bothering to take it seriously." Stepping into Un Regard Moderne, back when Jacques Noël ran it (he sadly passed away in 2016), was intense in all respects. That is, if you could even step inside, since he practically barricaded himself inside the 20 square metre shop with piles of books, zines and comics. I remember when I stood there in awe myself, shaking my little stack of "Smittekilde" zines wrapped in a poster. He payed for them in cash and hung the poster on a bookstand straight away. I of course immediately spent the money on other strange books, and walked away with a rare and powerful feeling that what I was doing matters.

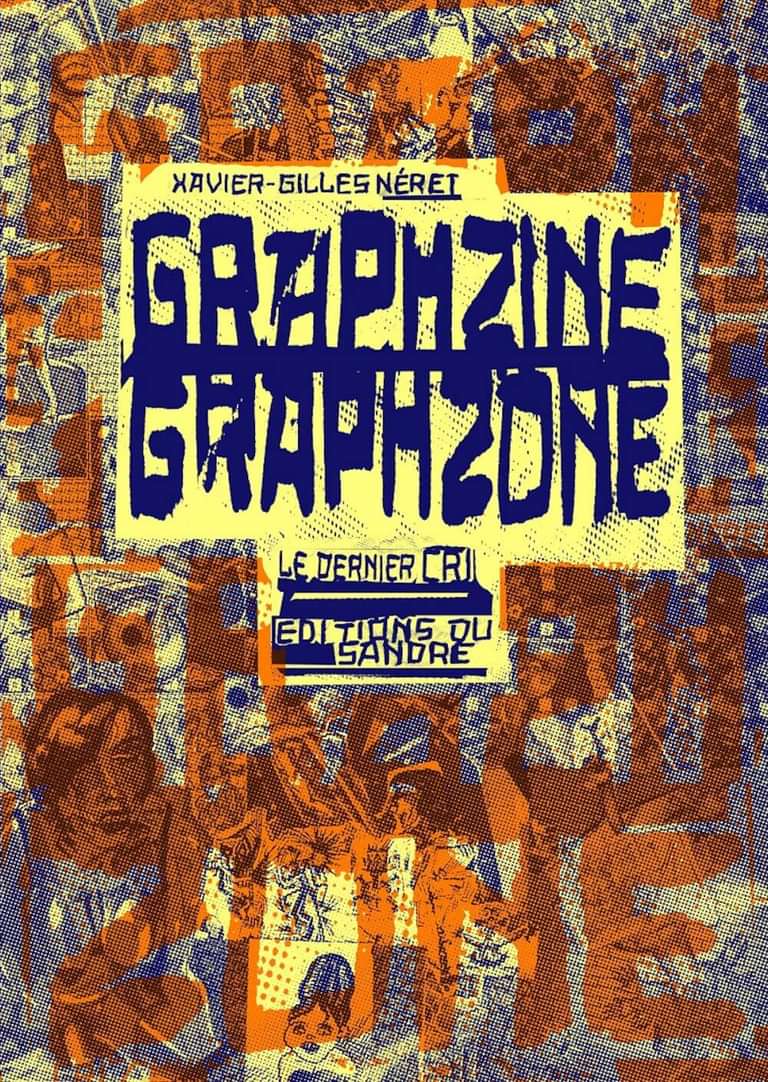

Graphzine/Graphzone by Xavier-Gilles Neret, published by SANDRE, 2019

Courtesy of the artist

Like all isms, trends and wider artworld phenomena, graph’zine culture was not something singular that came out of the blue. At the same time as Bazooka, several other Paris-based groups of graphic artists began to self-publish books and pamphlets as part of the punk wave sweeping the city. This outpouring of self-published printed matter also owed a great debt to the American underground “comix” scene, characterised by an abundance of satirical, violent, pornographic and psychedelic comics that all shared a sarcastic approach towards politics and religion, shunning the polished conservatism of the 1950s. The defining characteristic for graph’zine publishing, as opposed to the rest of this self-published material, lies in graph’zines emphasis on images with lines. Several key figures from history of the genre’s development attest to this in the book "Graphzine/Graphzone." Written by philosopher Xavier-Gilles Neret, the book is a thorough study of the phenomenon and is interspersed with references to art and literary history.

Another important influence comes from Japan, namely the Heta-Uma phenomenon (loosely translated to: being good at drawing badly), headed by artists like King Terry Yumura, considered the father of the "genre". He, like the American cartoonist Gary Panter, stands right at the forefront of the clash between free hippie attitudes and the violence of raw punk expression. In Japan, King Terry and several other cartoonists of the time published the magazine GARO, a heavily stylised response to the superficiality, perfectionism and guarded nature of post-war comics.

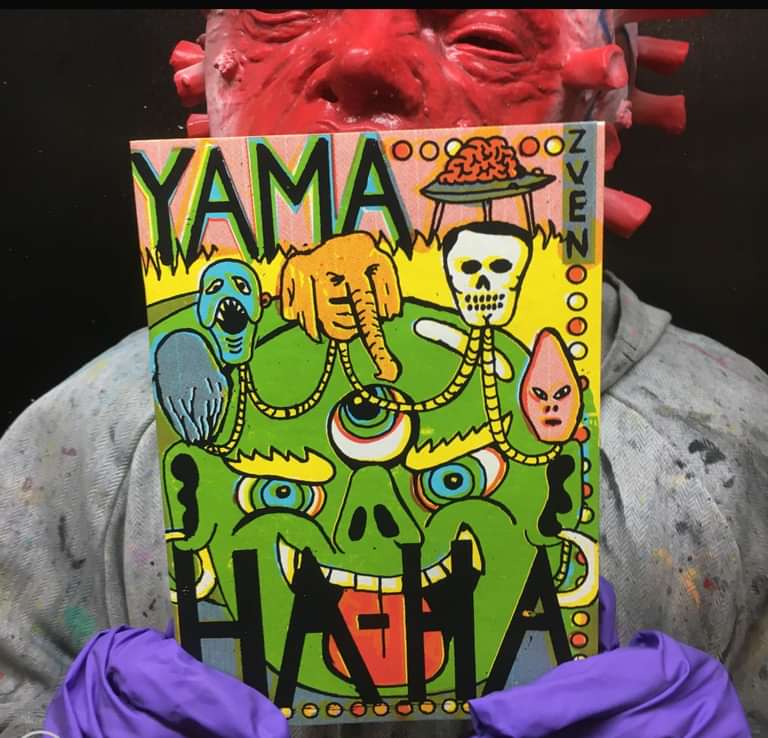

Yama-haha by Zven Balslev, published by Le Dernier Cri 2021

Courtesy of the artist and Le Dernier Cri

An important driving force for the development of both punk and zine culture has been a certain attitude of contempt towards the Establishment. In both England and France, class divisions are evident and arguably such visible separation has been a stimulus for "healthy" diverse counterculture, in this case in the form of zines. Since we in the Nordic countries still have a relatively inclusive and progressive cultural policy, this kind of contempt is difficult to cultivate, and therefore a similar tradition of counterculture is not as present in our social history. The increase in Nordic zine production in recent years however could be seen as an expression of a nascent hatred for the upper classes in the region. If you ask Anders Fjølvar, cartoonist, publisher and co-organiser of several important zine fairs in Copenhagen, he would classify all comics and zines as "literature for the working class."

If comics are a working-class art form, zine culture is just that little bit more free, chaotic and impossible for the institution to absorb, even if a publication like "Graphzine/graphzone" tries to encapsulate it. The many zine events that take place, merely require participants to have endured the ordeal of standing in line at the print shop, and long nights of stapling, folding and stacking. The content, or that which the booklets convey, allows room for everyone to contribute from amateurs, to children, queers, weirdos etc. – you name it. The zine community is a disorderly bunch that cultivates resistance precisely in the form of disorder.

Zven Balslev is a cartoonist, printmaker and publisher. He runs the Copenhagen based publishing house and graphic workshop Cult Pump. His latest zine "Yama-haha" is out from Le Dernier Cri.