Ditte Ejlerskov & EvaMarie Lindahl, The Blank Pages, 2014/2020 mdf shelves, Taschen Basic Art Series, 100 empty books, 4 shelves, each 240 x 120 cm.

Courtesy the artists and SPECTA

Growing up in a home without art books, my first introduction to 20th-century art was, weirdly, finding Sotheby’s and Christie’s auction catalogues in a box at my local charity shop in a post-industrial working-class town near Birmingham. These books were my entry to the recent greats. I had no idea who they were beyond a name, a title, a price, and an image. If I was lucky there would be a short text on the provenance of the paintings, which read to me like magic spells into a mystical other world. I was shocked years later to discover that Joan Miró and Jules Olitski were men. I had no idea that women weren’t included in the canon.

Throughout art school, I used the library daily. When I moved to London in 1997, I worked at Zwemmer Books, a legendary art book store on Charing Cross Road, opened in 1929. The store got sold and was taken over by new management. They talked about books ‘renting’ their space on the shelves. They asked questions like, Why do we have 5 books on Giotto? They wanted to shift books, flog them, get rid of them. They wanted piles of cheap, new, shiny books on display tables near the door, not expensive, dusty, old out-of-print books on dusty, old shelves. They wanted whizzy spinning cases filled with Taschen books.

The Taschen Basic Art Series was launched in 1985. It is still in print and is described by Taschen as “[a]n introductory who’s who of art history, architecture, and design, this series became the world’s best-selling art book collection ever published.” Most of the books—now counting nearly 200 titles—are monographs: “Each title from the Basic Art Series provides a comprehensive introduction to a significant artist, architect, or designer. The publications offer a detailed chronological summary of the artist’s life and work and analyze their historical importance and cultural legacy.”

If girls and women, non-Western, non-white, never see themselves depicted as geniuses, as groundbreaking, as change-makers, or even— imagine—merely as painters, why would they ever believe that they themselves could be?

10 years ago, Ditte Ejlerskov and EvaMarie Lindahl were looking at a few Taschen books in one of their studios and realised that out of over 90 books on artists, only 4 were on women. They called Taschen and spoke to an editor of the series, who responded that the reason that there were no books on women was basically because women artists of that calibre simply didn’t exist. Ejlerskov and Lindahl took this not as a rejection but as a challenge: “We realised this was going to be a big challenge and take a lot of research. We developed a methodology of finding female equivalents to the male artists in the series, based on success, recognition, geographical location, and time period. We started looking at books, encyclopaedias, auction results, records of museum shows, etc. This took 2 years. We matched women artists to the male artists in the book series, Friedrich, Leonardo Da Vinci, etc.” When they had compiled this list of women artists, they wrote back to the editor, informing her: “You asked if we were able to mention any female artists that we thought were missing. We mentioned a few that you did not acknowledge as potential candidates for Taschen’s version of art history. We hereby hand over our entire compilation of the nearly 100 missing female artists that we consider qualify for the Basic Art Series alongside the 92 men and 5 women already published.”

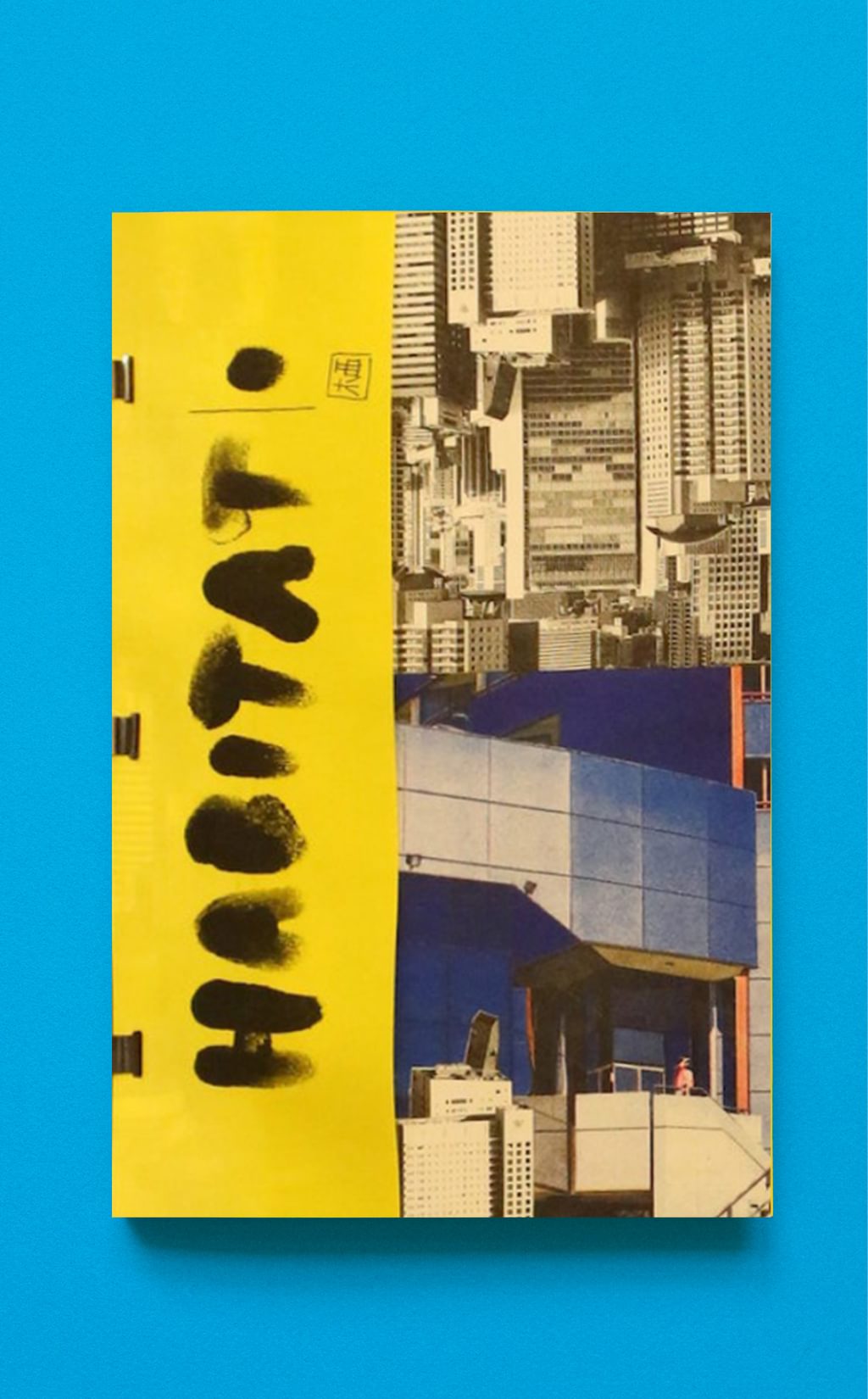

Ditte Ejlerskov and EvaMarie Lindahl, The Blank Pages, 2014/2020, installation view II.

Photo by Ditte Ejlerskov and EvaMarie Lindahl

By following the original Taschen selection process and matching women to the men who already had books made about them, they exposed more gaping holes in the writing of art history. They couldn’t add Chinese women artists, because no male Chinese artists were included in the original series. The same for Africa, most of South America, the Middle East, Asia. A useful trick for painters when assessing how a painting is developing is to look at it in the mirror. See the painting in reverse, and the errors you’d grown comfortable with suddenly jump out.

They designed and printed covers for the unpublished books on the 100 female artists: indistinguishable facsimiles of the Basic Art books. They even made an installation, displaying their new books with the existing, published books. The only difference being that the new ones were filled with blank pages. This history was unwritten. It largely still is.

Why does this matter? Visibility. If you don’t see yourself reflected back by the world, you don’t feel like you belong there. If girls and women, non-Western, non-white, never see themselves depicted as geniuses, as groundbreaking, as change-makers, or even— imagine—merely as painters, why would they ever believe that they themselves could be?

David Risley is an artist. He ran David Risley Gallery, in London (2002-2010) and Copenhagen (2010-2018). He was founding Co-curator of Bloomberg Space, London (2002-2005), Co-founder of Zoo Art Fair, London (2004), and Co-founder and Co-owner of CHART. He continues to write, curate, and develop projects with artists. He is developing a sustainability project for public-facing institutions.