For many people, the idea of commissioning a life-sized replica of one’s ex-lover remains a distasteful suggestion. Heartbroken in 1918, the Expressionist pioneer Oskar Kokoschka paid a costume designer to fabricate a doll in the likeness of his former girlfriend - the composer Alma Mahler.

Among his requests to the designer was a proviso that the mannequin come complete with teeth and a tongue… The dubious erotic urges that motivated the project eventually gave rise to those of artistic inspiration and the painter depicted the furry dummy in close to 100 paintings, drawings and photographs before eventually beheading it as part of a drunken ‘performance’ in his garden, years later.

Beguiled by this esoteric episode from art history, Soshiro Matsubara (b. 1980, Hokkaido; Japan) has repeatedly returned to the narrative of thwarted passion, obsession and object transference that underpins the Oskar & Alma story.

Adopting their romance and transforming it into an archetype of eccentric intimacy, the artist has abstracted from Kokoschka and Mahler a varied cast of forlorn characters who appear throughout his sculptures, paintings, drawings, installations and texts.

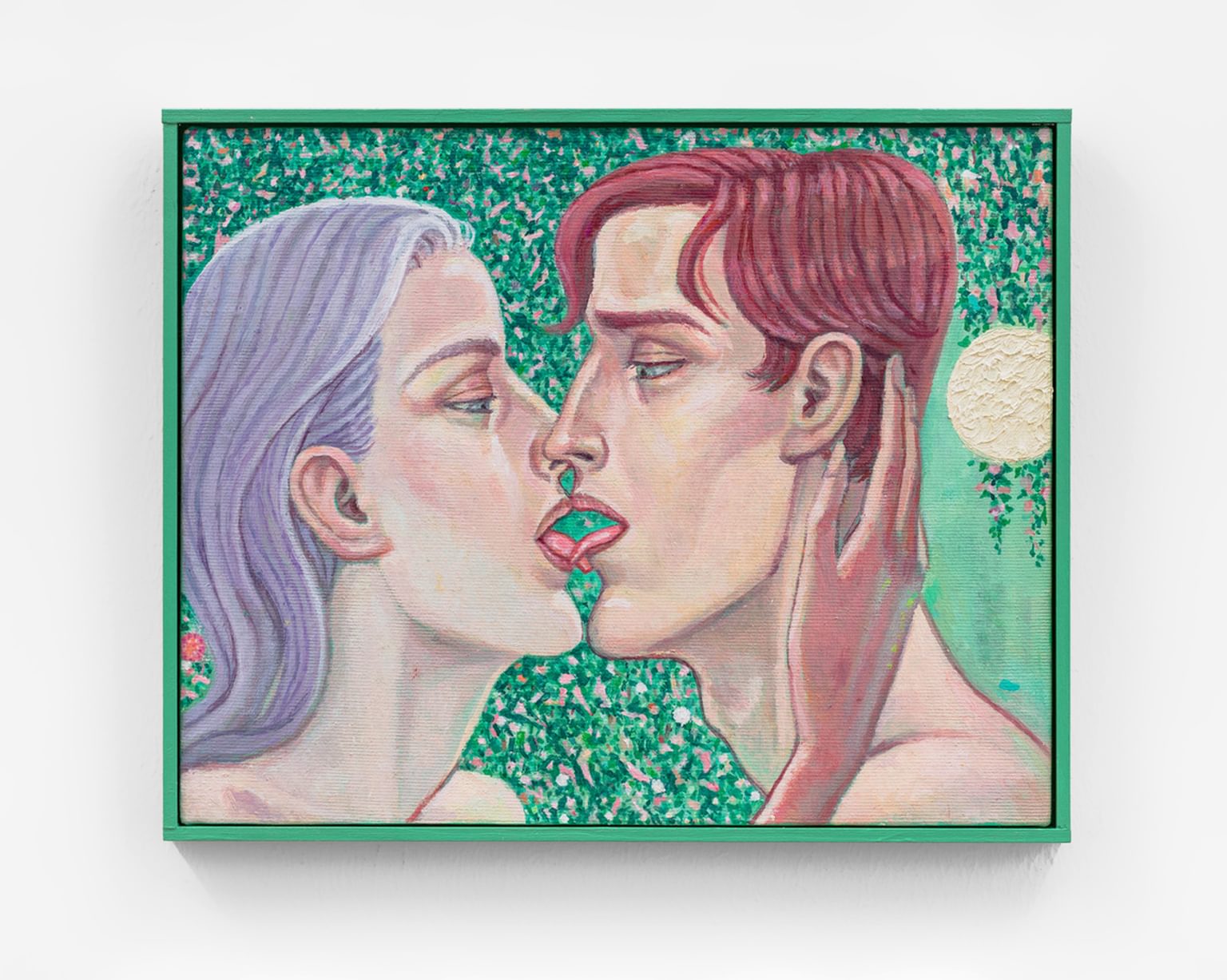

Soshiro Matsubara, Kiss XXII, 2020 courtesy of the artist and Croy Nielsen, Vienna

Photo by Kunst-dokumentation.com

Soshiro Matsubara, A Little Kiss, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Union Pacific

Photography by Reinis Lismanis

Soshiro Matsubara, Love Sick, 2019-2021, courtesy of the artist and Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw

Photo by Kunst-dokumentation.com

How might art objects mirror or even cultivate the experience of romantic love? This might seem like a strange question to ask in relation to a body of work that, in some ways, appears resolutely disconnected.

Matsubara presents disembodied ceramic heads and limbless torsos in the tradition of the classical marble bust, however most of his figurative sculptures have also undergone a process of uncanny enhancement.

Often sporting wigs of bright artificial hair and propped on top of podiums assembled from found objects, these reformulated bodies stare blankly at the viewer from behind glazed and despondent eyes.

Even when these fragmented figures are intertwined – embracing, kissing or positioned in a playfully macabre act of decapitated cunnilingus – a creeping sense of emotional detachment is compounded by the abundance of cool and hard surfaces and the absence of any animate sensuality.

And yet these sculptures also suggest a sense of frozen interiority – an understanding of what it requires to connect with other people and why withdrawing into a world of private fantasy might present an easier or more comfortable alternative.

Alone in their minds, these statues of assembled parts seem caught in acts of remembering and projection, embodying the piecemeal and detail-driven manner in which humans record impressions of intimacy to memory.

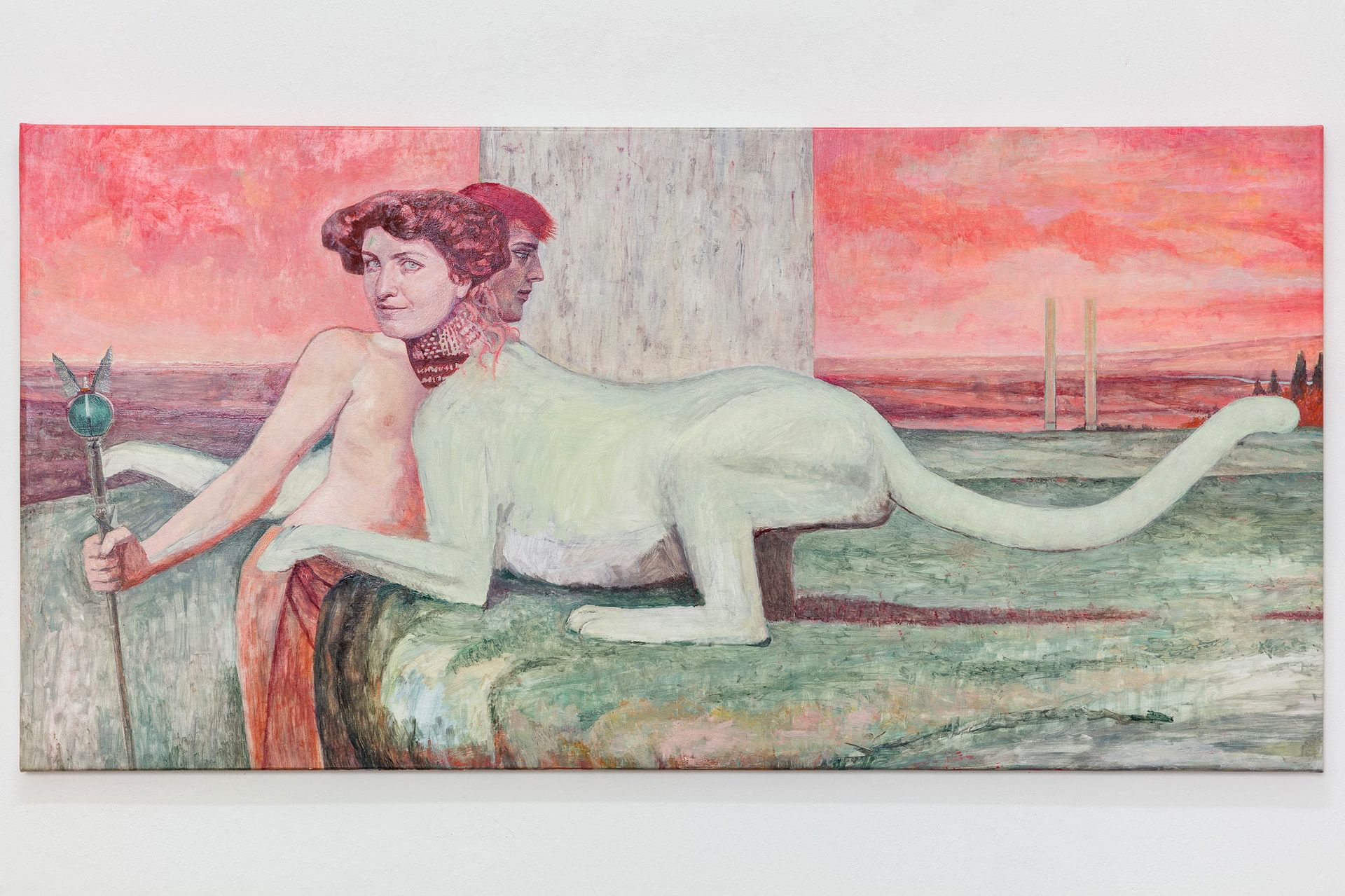

Soshiro Matsubara, The Caresses, 2020, courtesy of the artist and Croy Nielsen, Vienna

Photo by Kunst-dokumentation.com

This subtle but consistent interest in romantic inner life that seems so fundamental to many of Matsubara’s works, speaks directly to the artist’s parallel interest in Symbolist aesthetics.

Painters most closely associated with the movement, like Fernand Khnopff, often focused on problems of inner turmoil, using an ambiguous symbolic language to give representational form to mental images that could otherwise only be observed internally.

So too does Matsubara use an ornate language of symbols, featuring allusions to Greek mythological figures like Medusa and Hypnos (God of sleep) as well as iconic Symbolist masterpieces like Khnopff’s Carress of the Sphinx (1896), to materialise abstract moods relating to obsession and quiet yearning.

But it is not only from Khnopff’s work that Matsubara takes inspiration. Similar to the way in which he responds to and extends the saga that surrounds Kokoschka and Mahler’s passionate love affair, Matsubara also demonstrates a particular interest in Khnopff’s biography and the intensity of his relationship with his sister.

Explicitly his favourite model, Fernand Khnopff would look to Marguerite Khnopff continually throughout his life as he aimed to refine his artistic vision.

“In my opinion, Marguerite was a kind of prototype for Fernand Khnopff's ideal man or ideal woman” writes Matsubara, embodying Khnopff’s yearning for perfection in a way that “evokes the relationship between God and man.”

Lumière douce, like a never-ending déjà-vu / Fernand Khnopff, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Bel Ami

Photo by Bel Ami

Soshiro Matsubara, Last Night XLIII, 2022, installation view ‚Another Surrealism‘, Den Frie, Copenhagen, courtesy the artist and Croy Nielsen, Vienna

Photo by Mats Stjernstedt

Soshiro Matsubara Pure Silent II, 2022, courtesy of the artist and Union Pacific

Photo by Reinis Lismanis

Absorbing elements of Fernand Khnopff’s subject position and recontextualising them as part of his own aesthetic identity, Matsubara has adopted Marguerite’s visage as a recurring motif, often using it as a centrepiece in his iconic series of fallopian candelabra.

Here, Marguerite appears as a disquieting icon of watchful passivity and imaginary virtue - impressive in her statuesque majesty but also sombre and eery in her casting as an emblem of fetishism and fantasy.

Whilst Art History has conventionally sought to establish a framework for artistic production that divorces art objects from the personal lives of their creators, Matsubara foregrounds the strangely compelling biographies of other, principally canonical, artists as part of his own practice.

By lending his own creative agency to the lived experience of those who are no longer alive, Matsubara revitalises the stylised artistic expressions that such experience gave rise to; the inactive and all-to-familiar aesthetics we understand according to various schools of “ism” are thus brought back into the volatile world of ‘personal lives’ and unpredictable human behaviour.

Endowing artefacts that seem isolated from the social realm with inner life, Matsubara creates the potential for new meaning as he also risks the potential for more dissonant and sinister readings.

Soshiro Matsubara, Last Night XXII (L'Ange des splendeurs), 2021, courtesy of the artist and Croy Nielsen, Vienna / private collection Berlin/Hamburg

Photo by Kunst-dokumentation.com

Soshiro Matsubara often makes use of overly romanticized moments in art history, as means to examine the potential of art as a romantic pursuit or obsession.

Several pieces draw on the turbulent love affair between Oskar Kokoschka and Alma Mahler in the 1900s: upon being abandoned by Mahler, Kokoschka heartbrokenly had a doll fashioned in her image.

Filled with ambiguity and eeriness, Matsubara’s ceramics, paintings, and installations become emblems of the forces of attraction – from mad obsession to sensuous unions with the beloved. In 2017 he founded the antique shop 'Haus der Matsubara'.

Portrait by Marie Haefner